eBook - ePub

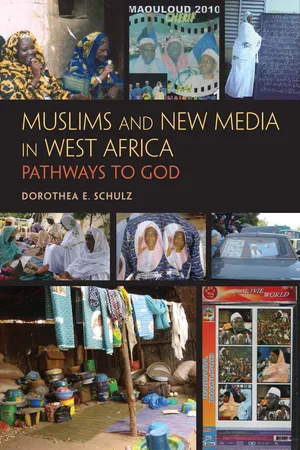

Muslims and New Media in West Africa

Pathways to God

Dorothea E. Schulz

This is a test

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Muslims and New Media in West Africa

Pathways to God

Dorothea E. Schulz

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Although Islam is not new to West Africa, new patterns of domestic economies, the promise of political liberalization, and the proliferation of new media have led to increased scrutiny of Islam in the public sphere. Dorothea E. Schulz shows how new media have created religious communities that are far more publicly engaged than they were in the past. Muslims and New Media in West Africa expands ideas about religious life in West Africa, women's roles in religion, religion and popular culture, the meaning of religious experience in a charged environment, and how those who consume both religion and new media view their public and private selves.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Muslims and New Media in West Africa est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Muslims and New Media in West Africa par Dorothea E. Schulz en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Théologie et religion et Théologie islamique. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Sous-sujet

Théologie islamiqueONE

“Our Nation’s Authentic Traditions”: Law Reform and Controversies over the Common Good, 1999–2006

IN MARCH 2000 Malian national radio announced in daily news broadcasts that a family law reform proposal, prepared by legal specialists and representatives of civil society, was to be publicly discussed so as to ensure popular participation and support. The projected reform of the codification of family law (Code du Mariage et de la Tutelle [CMT]), the broadcasts explained, was part of PRODEJ (Promotion de la Démocratie et de la Justice au Mali), a project financed by a consortium of Western donors to improve the effectiveness and credibility of the judiciary, and to mend inconsistencies within the Malian legal code “in accordance with international standards.”1 The anticipated law reform generated vehement protest among Muslim religious authorities and activists who publicly condemned the government’s endorsement of the Beijing platform as an attack on women’s “traditional role and dignity” that ultimately threatened to undermine Mali’s authentic culture, one “rooted for centuries in the values of Islam.”2 Yet the main targets of these Muslim leaders’ wrath, and their main political adversaries, were women’s rights activists who, in broadcasts aired on local and national radio and tacitly supported by the Family and Women’s Ministry, dismissed their protest as an attempt by “conservative religious forces” to pave the way for reactionary influences from the Arabic-speaking world by mixing religion and politics. Clearly, behind obvious differences in ideological orientation, Muslim activists and their political opponents have several points in common. Speakers on each side acknowledge that the government’s decision to reform Mali’s legal and judicial system is the result of various international influences and support structures, on the one hand, and of local and national political processes, on the other. Agendas of Western donor organizations intersect and collide with the interests of sponsors from the Arabic-speaking world, but also with interest groups struggling to gain greater influence in the national political arena. Both parties also present women’s dignity, and their rights and duties, as essential to definitions of the common good and of membership in the political community.

That each party casts questions of shared values and public order in a legalistic discourse that grounds political belonging in rights and entitlements echoes the ways that politics is realized throughout contemporary Africa and around the globe (Mamdani 2000; Shivji 1999; Englund and Nyamnjoh 2004; Werbner 2004, 263; see J. Comaroff and J. L. Comaroff 2000, 2004; J. L. Comaroff and J. Comaroff 2004). Imported together with other elements of the institutional and normative scaffolding of liberal democracy, Law has become a privileged modality of political intervention.3 Throughout Africa this development manifests itself in a mushrooming infrastructure of legal practitioners and extra-judicial structures, and in a panoply of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that act as supervisors of governmental politics and as promoters of a “politics of recognition” (Taylor 1992) cast in terms of legal rights and entitlements.4

The thriving of a legalistic discourse in contemporary Mali illustrates how this particular modality of political praxis in the national arena is produced in a global arena of politics and finances. The Malian law reform also reflects on how inconsistencies and paradoxes inherent in the model of the liberal nation-state play themselves out in the multicultural state politics of contemporary Africa. The model of the liberal state, based on the principle of an impartial treatment of religious and cultural diversity, is currently challenged by a heterogeneity of identities (J. Comaroff and J. L. Comaroff 2004; J. L. Comaroff and J. Comaroff 2004, 2006). In Mali, these challenges are cast in a moralizing idiom that centers on “proper” gender relations and thereby draws on long-standing discursive conventions (Schulz 2001b). What has changed is that conflicting constructions of belonging are expressed in a discourse of rights and entitlements. Whoever employs this discourse supports, and yet is simultaneously exposed to, the trappings of this form of political intervention; the language of rights in which the politics of recognition are nowadays cast inflates the significance of the legal domain in resolving issues of political participation and, even more important, in bringing about economic and social equity (Tomasevsky 1993; Kuenyehia 1994, 1998; Ilumoka 1994; Shivji 1999).

The aim of this chapter is twofold. It provides the historical backdrop against which contemporary interventions by Muslim activists and leaders into public debate, and their diverse relations to the state, need to be understood. It thereby retraces the historical process through which Islam has recently taken a central position in public debates on the moral foundations of the nation. The chapter then examines the particular stakes and forms of the politics of recognition that manifest themselves in the 2000 law reform debate, and analyzes the unintended consequences these struggles generated. Muslim leaders, by framing their challenge to official constructions of political belonging in the language of religious rights, capitalize on, and hint at, significant changes in the position of religion in the moral topography of the nation. In their efforts to frame religious identity as a matter of personal rights and entitlements, they present Islam as beyond, and unaffected by, the realm of politics, yet simultaneously reclaim it as central to their ethical self-understanding. Islam, in other words, becomes central in a politics of religious and moral difference.

Calhoun (1998) has critiqued communitarianism for its assumption that the common good is substantively defined and exists prior to historically constituted communities. This view, he argues, fails to address whose actors’ definition of the common good is made the normative basis of the political community, and where these actors are located in the social and political landscape (see Mansbridge 1998). What a political community accepts as shared normative foundations is the temporary outcome of a historically specific power constellation. Prevailing definitions of collective interest may not be a matter of common acceptance but a sign of the exercise of sovereign state power (Asad 1999). Struggles between unequal opponents center not only on substantive definitions of collective interest but also on the very right to participate in its definition. This right is determined by one’s location vis-à-vis state power, but it also depends on loci of power outside state control, such as religious authority, to which the government has to respond. How does the thriving legalistic culture in Mali empower particular interest groups—those that formerly could not partake in political processes but that now present themselves as bearers of certain cultural or religious entitlements—to seek public support for their visions of the common good? Why has Islam become such a powerful language of moral community, and why now? Answers to these questions will shed light on the ways neoliberal ideology translates into politico-institutional reform and, drawing on heavy financial and institutional support of Western donor organizations, generates unintended and paradoxical consequences.

Muslim Interest Groups and the State in Historical Perspective

Contemporary Muslim doctrinal disputes and competition over public recognition as representatives of civil society continue a long history of intra-Muslim controversy which, since the colonial period, has been fueled by the state’s ambivalent treatment of manifestations and representatives of religion in Mali’s public sphere. Rather than taking these ambivalences as a reason to deplore the discrepancy between the claims by the state to establish laïcité and its failure to realize this principle, my objective is to illustrate that, in the southern triangle of present-day Mali, historical attempts to articulate Islamic norms of public order and visions of collective interest were shaped by Muslim leaders’ mutual doctrinal contestation, and by their differential positioning vis-à-vis the colonial administration.5 Divisions among Muslims were reinforced by their unequal access to opportunities of travel and intellectual enrichment that were created by new technologies of transport and media and that intensified exchange with the Arabic-speaking world. The evolving “discursive capacities” of Muslims (Salvatore 1999) to formulate visions of public order and shape the moral topography of collective life were circumscribed, yet never fully determined, by colonial administrators’ efforts to control institutions and leading representatives of Islam. These efforts manifested themselves in the domain of education and in the colonial regulation of an emergent sphere of public discourse (Brenner 1993c; see Launay and Soares 1999).

Controversy among Muslim scholars over questions of how to order the life of the political community in accordance with Islamic principles predates the colonial period in Muslim West Africa. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, controversy often congealed in an interlocking of political and doctrinal dispute, as Islamic renewal took the form of militant jihad, and conformity with Islamic doctrinal prescriptions became a precondition for establishing political dominance. Disputes between Muslim leaders, often cast in a “Muslim discourse about truth and ignorance” (Brenner 2001, 133–144), highlighted questions of social justice, of authority in initiating a militant jihad and in ruling a theocratic state, and of the treatment of nonbelievers. Muslims’ competition over leadership was also reflected in their conflicting assertions of scholarly erudition and of special, divinely granted esoteric capacities (Last 1974, 1992; Robinson 1985, 2000; Levtzion 1986a, 2000; Brenner 1988, 1992, 1997). These controversies constituted the historical context within which the establishment of three important Sufi orders—the Qadiriyya-Mukhtariyya, the Tijaniyya, and the Tijaniyya Hamawiyya—since the late eighteenth century needs to be understood. French colonial conquest deeply affected Muslim debate with respect to the contents of doctrinal debate and its forms of articulation. These changes reflected challenges to the sources of authority and of political legitimacy that emerged from the reconfiguration of sociopolitical and economic fields under colonial rule. Doctrinal controversy and shifting power constellations among Muslims were also fueled by the overlapping effects of various local, regional, European, and Middle Eastern institutional connections and influences.6 Debates in the colonial French Sudan about Islam as a blueprint for social conduct had repercussions for broad segments of the population, as more and more people converted to Islam during this time. Muslim intellectuals of different orientations and educational background experimented with new institutions that were to enable modern Muslims to function in the social and political setting created by colonial rule and within the colonial and postcolonial political economy (Brenner 2001, 127–129; Triaud 2000). Still, in many areas, the Islamic civilizing traditions were of concern only to certain segments of the population until the 1930s and 1940s. The role of religious lineages as brokers between local producers and the colonial state was not nearly as important as it was in other West African countries, such as Senegal and Nigeria. Until the 1940s Muslims remained a minority in colonial French Sudan, except for some urban centers of religious erudition such as Timbuktu, Gao, Mopti, Djenne, Segou, and Nioro, that thrived under the influence of lineages associated with Sufi practice (e.g. Hanson 1996; Soares 2005).7 In some towns, the influence exerted by these lineages originated in precolonial polities and expanded in the colonial era.8 Particularly in the southern areas of Mali that became the post-independence centers of state administration and control, many converted to Islam only gradually.9 To the majority of these converts, being a Muslim was a matter of group and professional identity expressed in regular worship (zeli in Bamana; from the Arabic salat), a particular dress code, and food restrictions (Launay 1992).

San is a good illustration of the dynamics unfolding in colonial areas where Muslims long constituted only a minority. The (non-Islamized) Bobo and Bamana populations south and southeast of the town resisted French intrusion and the canton chiefs established by the colonial administration during the first twenty years of occupation.10 Until 1917, several insurrections were repressed with great bloodshed.11 In contrast, the few Islamized Marka, Fulbe, and Djenneké families who lived in San—some of whom claimed adherence to the Qadiriyya—and a few villages of the cercle were considered “loyal” to the “cause of the French nation” while forming “isolated” islands of Muslim practice among a “largely animist population” steeped in “superstition.”12 Although colonial reports expressed apprehension at the increased numbers of people converting to Islam,13 they assured administrative superiors in Bamako and St. Louis that there was no indication of a spread of “insurgent” ideas of pan-Islamism or of oppositional Muslim tendencies that were causing great concern in other areas of the French Sudan (e.g., Harrison 1988, chaps. 2, 5; Soares 2005, 51–60).14 Over subsequent decades, several politically powerful families in San converted to Islam. Yet, as local administrators condescendingly observed, “the level of religious knowledge” among the converted remained “very low” and was limited to the performance of the daily prayers.15 The limited spread of Islam in the area of San in the colonial period casts doubt on some claims formulated by proponents of Islamic moral reform, particularly their call for a “return” to the authentic readings of Islam. Others who participate in contemporary Muslim controversy today also appeal to a past consensus among the community of learned people (ijma) as the blueprint for present Muslim religious practice. This, too, is a somewhat nostalgic portrayal of past Muslim discourse. Throughout the colonial period, debates over ritual orthopraxy and the collective significance of Islam were shaped by actors with very diverging religious credentials.16 Among them were religious experts, scribes, and leaders from lineages with close ties to the Sufi order. Labeled marabouts by the colonial authorities, they benefited from the prestige associated with their genealogical descent and scholarly erudition. They were often supported by French colonial authorities who considered them representatives of a traditional African or “Black Islam” (Monteil 1980; see Harrison 1988, chap. 6) capable of limiting the influence of “radical” local Muslim reformers and of intellectuals who, from the 1930s on, challenged established religious understandings by referring to a universalistic conception of Islam that bore strong markers of a Salafiyya reformist discourse gaining currency in the Arabic-speaking world at that time.17

Various other actors also played a part in these debates. Some of them lacked genealogical pedigree but became religious self-made men by combining their various political, moral, and economic ambitions. Among them were those who could be called “political prophets,” that is, men who used their entrepreneurial skills to announce the immediate end of the world and mount attacks against the occupying powers.18 Others were labeled “ambulant preachers” by colonial authorities, who closely monitored their travels and proselytizing activities across West Africa because they feared the Islamism associated with the emerging pan-Arabic movement in the Middle East.19 Muslim scholars who preached under the tutelage of the colonial administration popularized understandings that placed special emphasis on the field of Islamic adab (Arabic, cultivation, manners). In so doing, they made this term central to their definitions of Islam as public norm, thereby partly reformulating the significance of adab (see Salvatore 1999).20 The effects of Muslims’ discursive interventions on common perceptions of Islamic norms depended in part on their relationship to the French colonial apparatus and administrators, and can therefore be seen as the paradoxical outcome of the administration’s monitoring of Muslim scholars’ proselytizing activities. By selectively supporting certain ambulant preachers, the colonial powers furthered a process in which Islam’s role as blueprint for social and moral action became accepted by a steadily expanding constituency of believers.

A parallel development occurred in the field of education, where the French encountered an organized resistance from intellectuals whose reformist initiatives were a direct response to their own attempts to streamline the making of colonial subjects. Administrators labeled these Muslims Wahhabi, a still widely used, yet also contested, term that contradicts the self-understanding of these intellectuals as Sunnis or ahl al-sunna wa’l-jama’a (Arabic, “People of the Sunna and the community [of the Prophet]”), that is, those who observe the regulations and doings of the Prophet Muhammad. Conversely, their self-portrayal as Sunni is considered an affront by other Muslims, because it implies their dismissal as nonbelievers. From the early days of their presence in the Soudan Français in the late 1930s, the Sunni reformists, many of whom had spent time in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, or North Africa, articulated an idiom of Islamic awakening. Though they differed in their priorities and in the local, regional, and Middle Eastern intellectual currents from which they drew inspiration (Kaba 1974, chap. 1; Brenner 2001, 140–152), they all attributed primary importance to the foundational texts of Islam and the example set by the community of the Prophet and his companions, thereby embracing central tenets of Salafiyya doctrine.21 Drawing on inspirational figures of Muslim modernist thought in the Middle East, the activities of these Muslim intellectuals—referred to by some as Al-Azharis because of their source of inspiration from Al-Azhar, the center of Islamic erudition in Cairo—were geared toward the articulation of an Islamic normativity in response to the institutions of the colonial state (Triaud 1986b; Brenner 2001, chaps. 2, 4). They provided a critical cornerstone to the traditions passed down by influential religious lineages, some of whose practices and beliefs they denounced as distortions (that is, as bida’ makrûha, unlawful innovations) of the original teachi...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Overture

- 1. “Our Nation’s Authentic Traditions”: Law Reform and Controversies over the Common Good, 1999–2006

- 2. Times of Hardship: Gender Relations in a Changing Urban Economy

- 3. Family Conflicts: Domestic Life Revisited by Media Practices

- 4. Practicing Humanity: Social Institutions of Islamic Moral Renewal

- 5. Alasira, the Path to God

- 6. “Proper Believers”: Mass-mediated Constructions of Moral Community

- 7. Consuming Baraka, Debating Virtue: New Forms of Mass-mediated Religiosity

- Epilogue

- Notes

- References

- Index