Economics

Fractional Reserve System

The fractional reserve system is a banking system in which banks are required to hold only a fraction of their deposit liabilities as reserves. This allows banks to lend out the majority of their deposits, creating new money in the form of credit. The system can lead to an expansion of the money supply and economic growth but also poses risks of bank runs and financial instability.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

6 Key excerpts on "Fractional Reserve System"

- eBook - ePub

101 Things Everyone Should Know About Economics

From Securities and Derivatives to Interest Rates and Hedge Funds, the Basics of Economics and What They Mean for You

- Peter Sander(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Adams Media(Publisher)

fractional reserve banking . Fractional reserve banking is a fundamental principle in modern-day banking whereby banks keep a fraction of their deposits in reserve and lend out the rest. Fractional reserve banking allows banks to stay in existence to make a profit on funds lent out. More importantly, in the aggregate, fractional reserve banking effectively creates more money for the economy.What You Should Know

Unless governed by the terms of a certificate of deposit, the money people have deposited in a bank can be withdrawn at any time. So how can a bank lend out money to others and earn a profit if it might have to return money to its depositors at a moment’s notice? Fractional reserve banking works on the theory that in all but the biggest crises, only a small fraction of depositors will want their money back.This idea then turns banks loose to lend out the rest—directly to customers or to each other. When banks lend money to each other, the borrowing bank can keep a fraction of that loan and lend to still others—customers or banks—and the cycle repeats. By keeping only a fraction of the money in reserve, banks can lend the same money many times over, effectively increasing the supply of money through leverage. In aggregate, the supply of money is thus a multiple of the “base” money created by deposits—or by injections from a central bank. In practice, the amount of money in circulation can be five, ten, or even twenty times the amount injected into the banking system by the Fed or individual depositors.This practice sounds risky, and indeed it can be, for if depositors see a crisis and demand all their money at once, it pulls the rug out from under the layers of leveraged loans. The Fed imposes a reserve requirement (see #36 Reserve Requirements - eBook - ePub

Credit and Creed

A Critical Legal Theory of Money

- Andreas Rahmatian(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

There can be no doubt that, in the most convenient use of language, all deposits are ‘created’ by the bank holding them…. But it is equally clear that the rate at which an individual bank creates deposits on its own initiative is subject to certain rules and limitations; – it must keep step with the other banks and cannot raise its own deposits relatively to the total deposits out of proportion to its quota of the banking business of the country…. the ‘pace’ common to all the member banks is governed by the aggregate of their reserve resources.Thus according to Keynes, banks also withdraw from their deposits at the central bank (‘reserve resources’) in order to lend money, though with caution in order not to upset the equilibrium between aggregate deposits and aggregate reserves. Only a ‘multiple deposit expansion’ (Paul Samuelson)13 allows the banks in aggregate to create money; an individual bank is unable to do that: the size of its loans is still confined to its deposits received. The Fractional Reserve System with its ‘money multiplier’ approach is typically discussed at length in economics textbooks, so that a brief outline suffices for present purposes, particularly since the legal theory of money put forward in this book does not accept the fractional reserve theory of money anyway, and even the Bank of England has rejected it fairly recently.1411 Quoted in Werner (2016: 364).12 Keynes (2013a: 25–26).13 Werner (2014b: 8).14 Bank of England (2014a: 15).Money creation through bank credit will be explained in detail below.15 The fractional reserve theory claims that money creation is restricted by the operation of the money multiplier. If customer A deposits cash, say 100, in a bank account, this does not have an effect on the money supply because the cash has been converted into a claim of customer A against the bank to pay out on demand.16 Then, according to the fractional reserve theory, the bank retains a certain amount of A’s deposit, say, 10% as reserves and lends out the rest, that is, 90, to B, by way of a cash payment. At this stage, the money supply is increased because in addition to the 100 as debt of the bank against A, 90 in form of cash are put into circulation. B can then use the cash to buy goods from C, and C may then deposit the received 90 in cash in his bank account (with the same or another bank). The bank holding C’s account can then take 90% of the 90 (10% are retained as a reserve) to lend these 81 to D, paying out in cash, and D can buy goods for 81, so that the recipient of 81 in cash can deposit that amount with his bank, which, in turn has 90%, or 72.9 available for a new loan. And so forth: 100 − 10% = 90 − 10% = 81 − 10% = 72.9 – 10% = 65.61 − 10% = 59.049. Thus the money supply has been increased from 100, the initial deposit, to 100 + 90 + 81 + 72.9 + 65.61 + 59.049.17 - eBook - ePub

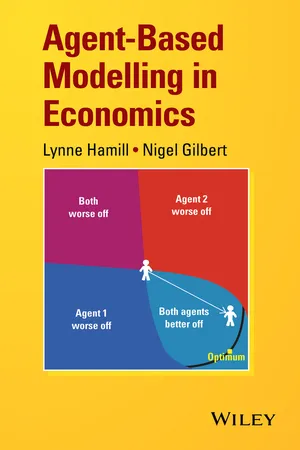

- Lynne Hamill, Nigel Gilbert(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

9 Banking9.1 Introduction

Banks are part of almost everyone’s lives in the United Kingdom: people use banks for everyday transactions, to hold their savings and to lend them money as indicated by the stylised facts in Box 9.1 . Banking is based on a powerful mechanism, fractional reserve banking, which is the focus of this chapter.Box 9.1 Stylised facts about borrowing, savings and banking by households in Great Britain.

Almost all households have a bank account.- Only 2% of adults ‘lived in households without access to a current or basic bank account, or savings account’ in 2008/2009 (HM Treasury, 2010).

- A third of households had no savings at all.

- 40% had savings of less than £10 000.

- About 20 had savings of £20 000 or more.

- A quarter of households had a mortgage on their main residence, on average £92 000 (ONS, 2011, p.18).

- Half of households had non-property related debt: on average £7000 (ONS, 2012, pp.13–15).

Fractional reserve banking

Fractional reserve banking allows banks to make money or, rather, create credit. Banks do this by ‘exploiting the fact that money left on deposit could profitably be lent out to borrowers’ (Ferguson, 2008, p.49). This is not new. It can be traced back to the founding of the Swedish Riksbank in 1656 and was described by Adam Smith in the eighteenth century (1776/1861, Book II, Chapter II).Fractional reserve banking works like this. The bank needs to hold a percentage of the sum deposited with it to meet day-to-day demand for cash withdrawals. This percentage is called the reserve ratio. If the reserve ratio is 10%, then the bank can lend out 90% of its deposits. So if a bank takes in £1000, then it is free to lend out £900. This means that there is now £1900. The recipient of the loan uses that £900 to buy something. The money is then passed to a retailer, who puts it in the bank. The bank then has another £900 deposited and can lend out a further £810 (being 90% of £900). The total money in circulation is now £2710 (being £1000 plus £900 plus £810). A fourth round adds a further £729, bringing the total to £3439. And so it continues, with less being lent out at each round. After about 50 rounds, there is less than £5 to lend out. But by then, the original £1000 has grown to almost £10 000. The bank deposit multiplier, which records the ratio of the total loaned out to the initial loan, is 10. This is illustrated in the figures in the top row of Box 9.2 , with the mathematics in the bottom row. To sum up, as a result of fractional reserve banking with a reserve ratio of 10%, an initial £1 000 can be increased to £10 000 (assuming that there is a demand for these loans). (For more on this, see, e.g. Begg et al - eBook - ePub

Money, Banking, and Financial Markets

A Modern Introduction to Macroeconomics

- Dale K. Cline, Sandeep Mazumder(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

From a practical standpoint, loan officers are authorized by upper management to make loans up to a certain amount, with that ceiling being determined based on the bank’s capital, granting them room to do business without being required to request specific permission to make each individual loan. So, assuming customer credit risk is being responsibly evaluated and managed, it is capital and leverage ratios, and not reserve requirements, that keep check on how rapidly a bank expands its loan portfolio.As we close this chapter, let’s remember that we have just made a departure from the story that is supported in academia, and moved toward the way money creation actually works in reality. For years, the economics profession has presented and argued in favor of the fractional reserve lending theory of money creation. While it makes for a nice numerical exercise—as we have presented in this chapter—if one deals with bank loans in the real world, this is not how it actually works. Instead, banks can create money by simply issuing deposits to their customers. So, in some sense, money is created out of thin air by banks, yet the system still contains appropriate checks and balances that limits the amount of money creation that banks are able to do. The Bank of England—the second oldest and one of the most widely respected central banks in the world—supports this very idea. - eBook - ePub

Money, Banking, and the Business Cycle

Volume II: Remedies and Alternative Theories

- B. Simpson(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

If America had a completely free market in its banking and monetary system, that is, if it had a banking and monetary system with no government deposit insurance; no government “lender of last resort”; no government examinations, assurances or inspections; no government imposed capital requirements, restrictions on competition or extended liability for bank shareholders; and no government provided fiat money and Federal Reserve, its banking system would be as sound and as stable as possible. The system would be based on a 100-percent reserve gold standard. This is the monetary and banking system of a free market. Such a system would create a rock-solid foundation on top of which economic progress could take place. Such a system would virtually eliminate the vicious cycle of boom and bust that has come to be known as the business cycle. In succeeding chapters I show just how a 100-percent reserve monetary and banking system would be achieved within the context of a free market in money and banking and how this system would create such a stable financial environment. At this point, I turn to why a free market would not lead to fractional reserves.WHY A FREE MARKET WOULD NOT LEAD TO FRACTIONAL RESERVESAs I stated at the start of the previous section, it is often believed that if banks were free to lend reserves on checking deposits, they would hold very little reserves backing such deposits. In fact, many who do not understand the nature of banking, and business in general, believe that banks would hold no reserves if they were legally allowed to do so. Regardless of the level of reserves it is claimed banks would hold, most people believe that banks would certainly hold significantly less than 100-percent reserves. As I have stated, it is my contention that this is not true. My claim is that a free market in money and banking tends to lead banks to hold 100-percent reserves on their checking deposits (and banknotes issued). I discuss in the next chapter just how it will lead to 100-percent reserves. In this section I focus on two points: why banks have the right to issue fiduciary media and why if this right is protected it will not lead to banks holding fractional reserves.Why Banks Have the Right to Issue Fiduciary MediaThe issuance of fiduciary media, by itself, does not violate individual rights.18 It can be performed in a way that is consistent with the protection and respect for rights. Some economists, such as Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Jörg Guido Hülsmann, and Walter Block, believe that the issuance of fiduciary media is in every case an act of fraud and thus a violation of individual rights. They state, “any contractual agreement that involves presenting two different individuals as simultaneous owners of the same thing (or alternatively, the same thing as simultaneously owned by more than one person) is objectively false and thus fraudulent.”19 - eBook - ePub

- Stuart I. Greenbaum, Anjan V. Thakor(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

However, required reserves are unavailable to meet deposit withdrawals. The reason is that any deposit withdrawal reduces available reserves, and the deficit must be made up. For example, consider a bank with $100 in deposits and a 5 percent reserve requirement against these deposits. Imagine that the bank has $10 in capital, so that the total asset base is $110. This bank is required to keep $5 in cash reserves. Imagine that it does so and invests the remaining $105 in other assets. Now, suppose there is a $5 deposit withdrawal that the bank meets with its reserves. Since it now has $95 in deposits, it needs to keep $4.75 in reserves. This will require taking in new deposits (note, however, that more than $4.75 in new deposits will be needed since the reserve requirement applies also to the new deposits) 45 or by liquidating other assets. 46 This is the paradox of fractional reserve requirements. Rather than augmenting liquidity, reserve requirements freeze assets into immobility. 47 The safety of any fractional reserve banking system rests squarely on the availability of a secure and reliable lender of last resort. Fractional reserve requirements cannot help much in this regard. More recently, reserve requirements have been rationalized as a tool of monetary policy. 48 In its 1931 report, the Fed Committee on Bank Reserves stated, “The most important function served by reserve requirements is the control of credit.” Since increasing reserve requirements means that a smaller fraction of deposits can be loaned out by the bank, the Federal Reserve can, in principle, affect the availability of credit by altering reserve requirements. As a practical matter, however, reserve requirements have played only a minor role in the Fed’s monetary policy

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.