History

1960 Presidential Election

The 1960 Presidential Election was a closely contested race between Republican candidate Richard Nixon and Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy. Kennedy ultimately won the election by a narrow margin, becoming the youngest president elected at the time. The televised debates between the two candidates were influential in shaping public opinion and are often cited as a key factor in Kennedy's victory.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

3 Key excerpts on "1960 Presidential Election"

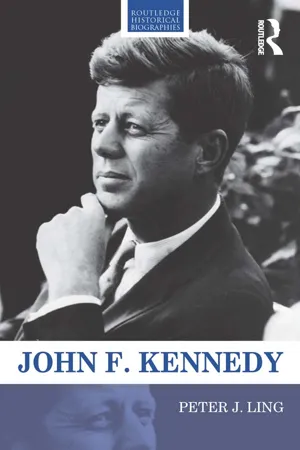

- eBook - ePub

- Peter J. Ling(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3 The 1960 campaignA good time to run

The four-year presidential election gap ensures that, every twenty years since 1800, Americans have chosen a president to lead them firmly into a new decade. On six consecutive occasions from 1840 to 1980 the president elected in this “zero” year died in office. Among them were the assassinated presidents Abraham Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley, and, of course, John F. Kennedy. Only Ronald Reagan's recovery from the gunshot wound he suffered in 1981 ended this fateful cycle. If the pattern was known to the politicians of 1960, however, it was a weak deterrent. On the Republican side, Vice President Richard Nixon was the clear front-runner, and he soon became the putative party nominee when his liberal rival, Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, declined to run. Rockefeller did, however, continue to cause problems for Nixon, as he strove to appease both Rockefeller liberals and right-wing Republicans, increasingly identified with Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater.On the Democratic side, the field was much more crowded. In the primaries Kennedy jostled for the nomination with liberal stalwart Hubert Humphrey, both men striving to prove their vote-getting potential. Since most primary contests in this period were nonbinding in their allocation of convention delegates, the nomination was not secure until the convention itself, and other contenders—Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas, Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri, and twice-nominated liberal standard-bearer Governor Adlai Stevenson of Illinois—positioned themselves for a move when the party gathered in Los Angeles. Stevenson in particular denied any wish for a third nomination, yet still hoped to be drafted by his convention supporters.The auguries for Democrats in 1960 were promising. First and foremost, the hugely popular Eisenhower was prevented from running for a third term by the Twenty-second Amendment, ratified in 1951. Ironically, it had been championed by the Republicans after the four consecutive terms of Franklin Roosevelt. But in 1960 it promised to benefit their opponents, since no Republican could match Ike's appeal. Four years earlier, in spite of Eisenhower's landslide victory, the Democrats had gained ground in Congress—two further seats in the House for a majority of 33, and one Senate seat for a majority of two in the upper chamber. The midterm elections saw further Democratic gains. Richard Nixon recalled election night in 1958 as one of the most depressing he had ever known. The statistics, he wrote later, “still make me wince” (Nixon 1978: 220). The Democratic majority swelled to 130 in the House and to 28 in the Senate. Admission of Hawaii and Alaska as full states of the union in 1959 confirmed Democratic dominance. Hawaii had one Republican and one Democrat in the Senate, but its sole congressman was a Democrat. Both of Alaska's senators and its solitary representative in the House were Democrats. - eBook - ePub

Unstable Majorities

Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political Stalemate

- Morris P. Fiorina(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Hoover Institution Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 10 The 2016 Presidential Election—An Abundance of ControversiesEven by the colorful standards of presidential primaries, the 2016 election cycle has been filled with jaw-dropping, head-scratching moments .—Eric BradnerWhile the world celebrates and commiserates a Donald Trump presidency, one thing is clear: this will go down as the most acrimonious presidential campaign of all .—Rachel ReveszControversial presidential elections are nothing new in American electoral history, 2016 being the latest, but certainly not the first. Despite much apocalyptic commentary, however, the implications of the 2016 election seem less dire than those of some elections held in earlier eras. The four-candidate 1860 election started the country on the path to civil war and the disputed election of 1876 threatened to reignite that conflict. In more recent times, the strong showing of a racist third party in 1968 coupled with political assassinations and civil disorders on a scale not seen since the labor violence of the early twentieth century led some contemporary observers to believe that the country was “coming apart.”1 The 2000 Florida electoral vote contest raged for more than two months, threatening a constitutional crisis and deeply dividing partisan activists on both sides. Still, even allowing for the fact that secession and revolution are not seriously on the table, for the sheer number and breadth of the controversies that accompanied it, the 2016 election does seem out of the ordinary.Parties have nominated flawed candidates before—Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964 and Democrat George McGovern in 1972, for example—but at least since the advent of scientific survey research, no major party has nominated a candidate so wanting in the eyes of the electorate, let alone both doing so simultaneously. Charges of ethnocentrism and racism are as American as apple pie, but in their prevalence and virulence in 2016 (with misogyny added to the toxic mix) they were reminiscent of 1928, if not the late nineteenth century.2 “Biased media” is a complaint common to all elections, but the retreat from objectivity by the mainstream media in 2016 struck many observers as a significant break with modern journalistic practices.3 The increasingly visible role of social media like Twitter threatened to further diminish the importance of the legacy media. Swing voters, largely missing in action in recent elections, suddenly reappeared in 2016.4 Possible foreign intervention in the election was a new development (at least insofar as the United States was the intervenee rather than the intervener), as was FBI involvement (but possibly only because earlier instances did not become public). Meanwhile journalists scrambled to read up on “populism,” which had not played such a significant role in American elections since the 1960s. “Class,” long ago displaced by discussions of race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation in college course syllabi, enjoyed an academic as well as political revival (so did “authoritarianism,” another oldie but goodie).5 - eBook - ePub

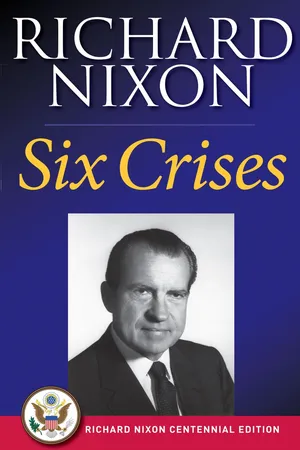

- Richard Nixon(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Simon & Schuster(Publisher)

SECTION SIX

The Campaign of 1960

The most dangerous period in a crisis is not in the preparation or in the fighting of a battle, but in its aftermath. This is true even when the battle ends in victory. When it ends in defeat, in a contest where an individual has carried on his shoulders the hopes of millions, he then faces his greatest test.ON November 9, 1960, I joined a select group of four living Americans—Herbert Hoover, Alfred M. Landon, Thomas E. Dewey, and Adlai E. Stevenson—who have sought the Presidency of the United States, as the nominee of one of the two major parties, and who have lost.I will not try here to tell the complete story of the campaign of 1960. This entire book, and even more, would be required to do that. And I would be the first to admit that the candidate himself is least able to treat the subject objectively.What were the major decisions that affected the outcome? How and why were these decisions made? What are the reactions of the candidate, his wife, his children, his friends, as they realize that the longest, hardest, most intensive campaign in American history has ended not in victory but in defeat—and by the closest margin in this century?Years of effort go into the planning and execution of a presidential campaign. But in the end, only a few hours prove really to have mattered. Millions of words are written and spoken, but only a few phrases—usually unpredictable at the time—affect the result.So often is the candidate confronted with crises and decisions that they become almost routine. Preparing a major speech, approving a key platform provision, holding an important press conference, debating with his opponent—any one of these events may prove to be crucial in a close election.So I will try here merely to highlight those few hours, words, and decisions that from my vantage point, as the losing candidate for President in 1960, had the greatest effect on the result.I admit at the outset to some understandable bias. Some of the flash output that was rushed into print immediately after the campaign made me wonder if the writers were reporting the same campaign I had just lived through. I am also aware that many of my friends and supporters sincerely (and in many cases even angrily) believe that if only I had followed their advice in the campaign, the infinitesimal margin by which Kennedy was declared the winner would have been overcome and I would have been elected.

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.