History

Advantages of North and South in Civil War

The North had advantages in terms of population, industry, and transportation, which allowed them to produce more resources and sustain a longer war effort. The South, on the other hand, had advantages in terms of military leadership and familiarity with the terrain, which initially gave them an edge in battle. These advantages played a significant role in shaping the outcome of the Civil War.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

5 Key excerpts on "Advantages of North and South in Civil War"

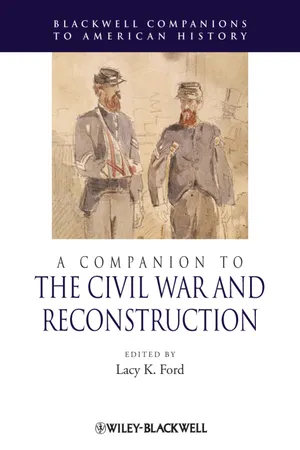

- eBook - ePub

- Lacy Ford(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Richard Current seemingly set himself apart from the others from the start, accepting the southern argument that northern resources proved so overwhelming that itsvictory was inevitable. Indeed, he suggested that perhaps historians should ask: “How did the South manage to stave off defeat so long? Or perhaps the question ought to be: Why did the South even risk a war in which she was all but beaten before the first shot was fired?” (Current 1960: 15). The South believed that the odds facing the Americans in 1776 and in 1812 were “as bad or worse” than those the Confederacy faced in 1861, Current asserted, and since they defended their homes, the South also held an important psychological edge. But, the South sorely lacked the economic infrastructure to win. “For the North to win, she had only to draw upon her resources as fully and as efficiently as the South drew upon hers; or, rather, the North had to make good use of only a fraction of her economic potential” (Current 1960: 30). The North’s vast “productive ability made the Union armies the best fed, the best clothed, the best cared for that the world ever had seen.” In short, “God was on the side of the heaviest battalions” (Current 1960: 31, 32).The four other contributors accepted the notion that Confederate victory was at least possible. T. Harry Williams compared the military leadership of both sides, an intriguing subject since the generals on both sides “were products of the same educational system and the same military background” (Williams 1960: 35). Since most of them had learned about the art of war from West Point Professor Dennis Hart Mahan – a disciple of Swiss military theorist Antoine Henri Jomini – they worked from the same set of premises. Even though Bigelow (1890) and Steele (1909) had plowed this ground before, Williams introduced the wider Civil War community to Jomini’s ideas, stressing his emphasis on the superiority of the strategic offensive and his four strategic principles: first, targeting decisive points in a theater of war, maneuvering the bulk of one’s own force against them, and protecting one’s own communications and threatening those of the enemy; second, maneuvering to engage portions of the enemy with the bulk of one’s own force; third, on the field of battle, identifying the key points and overwhelming them with the bulk of one’s own force; and fourth, using concentrated forces speedily and simultaneously. Since West Point graduates commanded both armies in 55 of the Civil War’s 60 greatest battles and led one of the armies in the other five, Jomini’s impact on Civil War generalship could not be doubted. - eBook - ePub

Understanding Civil Wars

Continuity and change in intrastate conflict

- Edward Newman(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

31A less popular account of the roots of this sectarianism explores immigration patterns in order to explain the background to the civil war, and to explain patterns of fighting in the war. According to this, the cultural distinctions can be explained by groups with different European traditions tending to emigrate to and be concentrated in the south and the north.32 Certainly, those fighting on both sides displayed a significant level of awareness and commitment to their political cause;33 the civil war combatants were ‘ideological armies’.34It was a relatively literate citizenship from which the forces were drawn, and the personal testaments of the time from those engaged in combat display a remarkable level of ideological motivation.35 This also helps to explain the perseverance and sacrifice of combatants which characterized the war, in the face of very high levels of casualties over a prolonged period. The motivation of fighters on both sides – ordinary people who voluntarily took up arms – demonstrates a strong sense of idealism and a commitment to freedom, a sense of self-sacrifice for future generations and in defence of principles. In the north, men volunteered in defence of the flag, the union, the constitution and ‘democracy’.36 Southern protagonists expressed a passion for independence, resistance to invasion by alien forces, pride in the principles and civilization of the south, and a genuine sense of fighting for their homes and families in defence against invasion: ‘The prospect of subjugation sustained Confederate soldiers in their dedication to the southern cause.’37 A Georgian planter-turned-army officer recorded: ‘We fight not only for our country – her liberty and independence, but we fight for our homes and firesides, our religion – everything that makes life dear.’38 It is a great irony of the war, as an eminent historian of this conflict observes, that both sides genuinely believed that they were fighting for freedom.39 - eBook - ePub

A Savage War

A Military History of the Civil War

- Williamson Murray, Wayne Hsieh(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 13 The Civil War in HistorySurely a just God will punish these Northern fanatics for the misery and death they are spreading over our land. Yes, a day of retribution must come when they shall be made to feel the curse of their own evil doing. I sometimes wish that the earth might engulf them as the wicked were in the Red Sea.—Jesse Sparkman (quoted in Joseph Glatthaar, General Lee’s Army)Was the victory of the North inevitable? To look at the results of 1865 and the overwhelming strength that by the war’s end the North deployed against the Confederacy and then to conclude that the results were inevitable is to remove the role of contingency and human factors from the history of the war. Viewed from April 1861, the Union’s triumph was by no means certain. The Confederacy possessed important advantages. The extent of its territory, continental in its expanse, at least in European terms, the commitment of most of its white population to the cause of independence, and the economic weapon that cotton provided, all represented major advantages. In addition to the distances with which Union armies would have to come to grips, there was the wretched state of unimproved roads throughout the Confederacy.On the other hand, substantial portions of the Northern population, at least before Sumter, preferred to see the Confederate states go in peace and were hardly willing to support a great war for the Union. As the war dragged on, violent outbreaks of Northern resistance—the most spectacular being the New York City draft riots of 1863—to intrusive military mobilization underlined the limits of Northern commitment. But perhaps most daunting of all was the fact that no one in the North at the war’s outbreak had a clue as to the difficulties that the translation of the North’s advantages in population and economic strength into military power would confront, much less the price that a successful war for the Union would demand. The political and strategic conduct of the war would require extraordinary leadership and therein lay the great imponderable on which success or failure in the Civil War, as in all conflicts, rested. - eBook - ePub

- Allan R. Millett, Peter Maslowski(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Free Press(Publisher)

Decades of sectional disagreements over the expansion of slavery into the territories and, for a small minority of northerners, the moral implications of the institution, fueled sharp differences over states’ rights versus national authority and propelled the divided nation toward that fateful moment in Charleston Harbor. Once war became a reality, many people on both sides offered predictions regarding its probable duration and who would triumph. Few, however, foresaw exactly what the war would be like. Most people optimistically predicted a brief conflict waged with the romantic heroism of a Sir Walter Scott novel. Instead, the outlines of modern total warfare emerged during a four-year ordeal. Since both sides fought for unlimited objectives—the North for reunion and (eventually) emancipation, the South for independence and slavery’s preservation—a compromise solution was impossible. No short, restrained war would convince either side to yield; only a prolonged and brutal struggle would resolve the issue.As the North and South pursued their objectives, sheer numbers of men and industrial capacity became extremely significant. One Confederate general wrote that the war became one “in which the whole population and whole production of a country (the soldiers and the subsistence of armies) are to be put on a war footing, where every institution is to be made auxiliary to war, where every citizen and every industry is to have for the time but the one attribute—that of contributing to the public defense.” Neither belligerent could depend upon improvised measures to equip, feed, and transport its huge armies. Men with administrative skills working behind the lines were equal in importance to men at the front. Furthermore, the coordination of logistical and strategic matters on a vast scale could not be left to individual states. Massive mobilization required an unprecedented degree of centralized national control over military policy.Mobilizing for War

The North’s warmaking resources were much greater than the Confederacy’s. Roughly speaking, in 1861 the Union could draw upon a white population of 20 million, the South upon 6 million. Two other demographic factors influenced the numerical balance. First, the South contained nearly 4 million slaves who were initially a military asset, laboring in fields and factories and thereby releasing a high percentage of white males for military service. However, after 1862–1863, when the North began enlisting black troops, the slaves progressively became a northern asset. Second, between 1861 and 1865 more than 800,000 immigrants arrived in the North, including a high proportion of males liable for military service. Approximately 20 to 25 percent of the Union Army’s men were foreign-born. Ultimately more than 2 million men served in the Union Army, which reached its peak strength of about 1 million late in the war. Perhaps 750,000 men fought in the Confederate Army, which had a maximum strength of 464,500 in late 1863.11 - eBook - ePub

Rethinking the Civil War Era

Directions for Research

- Paul D. Escott(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

2Understanding Societies in War Challenges and OpportunitiesJust as enormous effort has gone into understanding the roots of the war, historians have energetically investigated the social and political history of the Union and the Confederacy. With the rise of the “new social history” and with greater attention to gender and cultural developments, there has been little danger that wartime society would be neglected in Civil War research. Here again the quantity and quality of work in recent decades are impressive. Although some might wonder what directions are left to explore, a few scholars have called for research in some neglected documents—the Provost Marshal Records, medical corps reports, and military tribunals of the US Army—and as Mark Neely has demonstrated, some large documentary collections contain gems that have been overlooked. Even without the attraction of such documentary sources, the possibility of understanding better the Northern and Southern societies in war is an exciting area for research.1Considering the war years from a general perspective, both the North and the South struggled onward through four bloody years while also experiencing significant internal difficulties. For both regions, persistence and internal division were realities that can give thematic unity to our narratives. Both sides seem to have expected a short conflict and easy victory, and both were mistaken. The North as well as the South had to adapt, innovate, and find the means to continue fighting. In the process, however, internal problems and divisions—social and political—appeared, and they were serious. Though we should never minimize the distress and human suffering of the war years, the difficulties that affected the wartime societies can offer an attractive intellectual challenge for historians. They also have relevance for today’s world.War is a crucible in which unusual conditions or intense pressures can put society to the test. War brings unexpected change, introduces new ideas, and almost always imposes strains on a social system that may have seemed to be in equilibrium. In the process, societies under stress reveal much about their structure, reigning values, and centers of power or protest. For the historian, the events of war present an opportunity to understand in greater depth the nature of society in both the North and the South. The scope of the Civil War meant that both regions were going to experience change, division, and conflict. Analysis of wartime developments thus is an exciting area for scholars, who have the chance to benefit from greater insight but also face significant challenges.

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.