History

African Americans in WW2

African Americans played a significant role in World War II, serving in segregated units and facing discrimination both at home and abroad. Their contributions helped to challenge racial segregation in the military and paved the way for the civil rights movement. The war experience also led to increased activism and demands for equality and justice within the African American community.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

5 Key excerpts on "African Americans in WW2"

- eBook - ePub

- Matthew S. Muehlbauer, David J. Ulbrich(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

African Americans during the Second World War have received more attention than any other period in U.S. military history. In his official Army history, Ulysses Lee (1966) recorded problems and contributions of African Americans in segregated units. Neil Wynn (2010) offers a brief overview of the Second World War in which he avers that the wartime experiences of African Americans played significant parts in the longer struggle for civil rights.Arguably the most recognizable African Americans in the Second World War were the “Tuskegee Airmen” of the U.S. Army Air Force. According to Stanley Sandler (1998), the training of black pilots started as an experiment because racial prejudices caused skepticism among white officers regarding black pilots’ skill and intelligence levels. African American pilots of the 332nd Fighter Group slowly garnered respect from their white counterparts because of their skills as fliers and courage during combat. Sandler emphasizes that the 332nd’s pilots felt constant pressure to meet higher standards than required of white pilots.Histories of other African American units include books by Mary Pat Kelly (1995), Melton McLaurin (2009), and Gina DiNicolo (2014). The authors tell similar stories of blacks confronting racial discrimination in American society and its military and later facing danger on battlefields. This struggle came to be known as the “Double V”—victory over racism at home and overseas. Authors have written about black individuals attempting to advance through the ranks, such as biographies of Benjamin O. Davis Jr. by Marvin Fletcher (1989) and Daniel “Chappie” James Jr. by James McGovern (2002).Despite the valor in combat by black units, historians have found that nine out of ten African Americans in the U.S. military found themselves relegated by discriminatory policies to menial support roles (Ulbrich, 2011). Menial did not equate to meaningless, however, as evinced by the appraisal of the “Red Ball Express” by David Colley (2000). This logistical effort saw six thousand trucks carrying 12,500 tons of supplies race across France to support the U.S. Army every day during late 1944. African American soldiers made up 75 percent of the truck drivers. - Robert Harris Jr., Rosalyn Terborg-Penn(Authors)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

WORLD WAR II: A SEGREGATED MILITARYLarge numbers of African Americans entered the armed forces during World War II, where they served in segregated units. In 1948, by presidential order, the military services were finally desegregated. Since that time, African Americans have played a critical role in the military, and the military in turn has come to occupy an important place in the postwar black experience. In some ways the military has been at the forefront of social change. Although problems of racial discrimination have not been totally resolved, the American armed services have offered greater opportunities for blacks in recent years than many other sectors of society.The “recruit / reject syndrome” is a common theme in studies of the early war experiences of African Americans. That is, in times of war African Americans were recruited into the military, and after war their service and their earned benefits as veterans were rejected. This theme is found in studies of the nearly five thousand African Americans who fought on the side of the colonists in the battles of Lexington, Concord, Ticonderoga, and Bunker Hill during the American Revolution; the 390,000 African Americans who fought for the Union during the Civil War; and the first all-black division, the 92nd Infantry, created during World War I.This trend would begin to change during the years of American involvement in World War II (December 1941–September 1945), as African Americans began to serve in the military in larger numbers and in a variety of roles. There are several reasons for the dramatic increase in the number of African Americans in World War II. For one thing, the country’s attitude toward racial oppression was changing. Although African Americans were forced to serve in racially segregated units, racial oppression in the United States and in other parts of the world fell under heavy criticism. From the very beginning, World War II was a battle against racial supremacy; the ideologies of Nazism, fascism, and totalitarianism were under severe attack. And, as in previous battles, African Americans reasoned that through participation in the war effort they would be accepted as first-class citizens after the war.- eBook - ePub

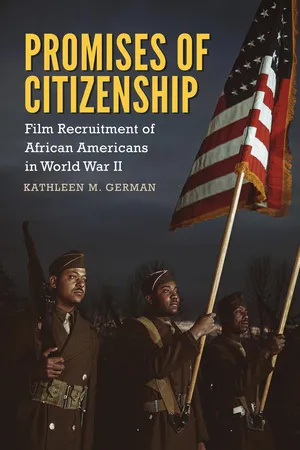

Promises of Citizenship

Film Recruitment of African Americans in World War II

- Kathleen M. German(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- University Press of Mississippi(Publisher)

CHAPTER SIXMilitary Conditions during World War II

The world’s greatest democracy fought the world’s greatest racist with a segregated army .—STEPHEN AMBROSE 1An overview of United States military history quickly reveals the discrepancy between the principle of harmony touted in The Negro Soldier and the reality of military exclusion. With few exceptions, white Americans in uniform have separated themselves from black Americans since the founding of the nation, mimicking the racial divide of the larger society.2 The armed forces have followed this racial division, generally discouraging or outlawing black participation. Only under the dire circumstances of war, when manpower shortages dictated that blacks be allowed into military service in order to avert defeat, were blacks allowed to serve their country. The conditions in which African American troops served during World War II were multilayered and complex, involving historical traditions of racial segregation, white and black attitudes, eruptions of civilian and military violence, and the realities of wartime. This chapter examines the evolution of military enlistment practices and the structural barriers that blocked African Americans from unconditional participation in military service.Evolution of Military Enlistment Policy

According to the earliest records, both enslaved and free blacks participated in North American military actions starting with the 1528 ill-fated expedition of Panfilo de Narvaez, whose slave Estebanico traveled though northern Mexico sending back reports of golden cities, and continuing to the current conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. The first law sanctioning a militia group was passed in 1607, as colonies organized for self-defense against the Native American threat. This original legislation made no reference to race, but by 1639 Virginia had enacted a bill excluding blacks from acquiring arms or ammunition as part of their militia participation. This ban was possibly adopted in response to the increasing number of slaves who, it was feared, would slaughter their masters if armed. The Militia Act of 1792 required every able-bodied citizen to defend the nation. Because militias were controlled by the colonies and later by the states, the practice of raising, training, and supporting militias continued to be patchwork at best. One condition was commonplace, regardless of otherwise inconsistent policies: There was widespread discrimination. The bottom stratum of society was over-represented in the lowest ranks, while sons of wealthy families populated the highest ranks and officer corps.3 - eBook - ePub

Africans and the Holocaust

Perceptions and Responses of Colonized and Sovereign Peoples

- Edward Kissi(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3 Africans and World War IIIt is now part of conventional knowledge that the “history” of warfare is more than the story of the soldiers who actually fought on battlefields. It is also the story of the perceptions of war, war propaganda, and the use of war by people who did not fight in it as a conduit for moral conversation.1 The published accounts of the involvement of colonial subjects from Africa in World II are vast. Those that directly relate to the subject of this book have already been reviewed in the introduction. Much of that literature and more beyond it examines the recruitment and deployment of colonial subjects for military service at various theaters of the war, the various war charities set up in the colonies to gather monetary and material contributions to the war effort, the courageous exploits of African soldiers in the service of the Allied Powers, and the disappointments that these soldiers faced when they returned home after the war.2This chapter takes a different angle of analyses from the orthodox approaches in the existing Africanist historiography on the war. It looks at the gathering clouds of war in the 1930s and how Africans understood and interpreted them, how colonial regimes explained the origins and the purpose of war against Nazi Germany and its allies, and how the colonized and sovereign peoples of Africa viewed the Allied explanations and what was at stake for them. The chapter shifts the story of Africans and World War II from the historiography’s dominant focus on how colonial subjects fought the war, or contributed money and materials to it, to an alternative analysis of how Africans, both subject and sovereign, thought about the war, assessed its meaning, and used it as a framework for challenging colonialism and also articulating their own concepts of civilized and ethical conduct in human interactions. Understanding the views and reactions of colonial subjects in Africa and the continent’s two sovereign nations (Ethiopia and Liberia) to World War II requires a new analytical approach: an intellectual and diplomatic history of the Second World War from an African perspective. This chapter provides that. It reaffirms an acknowledged fact in the historiography of the Second World War, as it relates to Africa, that for many people on the continent what became known as “World War II” began much earlier in Africa than it did in Europe with the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.3 - eBook - ePub

- Mark Ledwidge(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

29 and international race relations. African-Americans’ response to the plight of Britain and France in the face of German aggression was affected by both nations’ failure to aid Ethiopia and their perception of British and French imperialism, which subjugated millions of people of African descent worldwide.While Nazi ideology hailed the alleged superiority of the white race, African-Americans felt that European and white American views on race were not altogether dissimilar to those of the Nazis.30 Although African-Americans acknowledged that allied racism was less pronounced than Nazi extremism, they recognised that ‘the world of the 1940s was still by and large a Western white-dominated world. The long-established patterns of white power and non-white powerlessness were still the generally accepted order of things.’31 Given Britain and France’s enslavement and colonisation of African people, African-Americans and AAFAN viewed the struggle between the Allies and Axis Powers as an internal fight between white imperialists, with both sides intent on dictating the affairs of people of African descent and people of colour.32 Thus, Max Yergan stated to Du Bois: ‘the present war is the central fact in the world today. In my opinion, it is a conflict waged, among other purposes, to enable powerful [white] administrations to continue and extend their control over colonies and their inhabitants. This is true whether the victors are imperialist Britain and France or Nazi Germany.’33

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.