History

Angkor

Angkor was a powerful and influential ancient city in the Khmer Empire, located in present-day Cambodia. It was the political, religious, and cultural center of the empire, known for its impressive architecture, including the iconic Angkor Wat temple complex. At its peak, Angkor was one of the largest pre-industrial cities in the world, showcasing the Khmer civilization's advanced urban planning and engineering skills.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

5 Key excerpts on "Angkor"

- eBook - ePub

- Katherine Brickell, Simon Springer(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The temples and surrounds of Angkor were placed on the World Heritage List in 1992, but the call for a World Heritage listing for the monuments and temples of Angkor emerged in the late 1980s, concurrent with the changing political scene within Cambodia and the Paris Peace Accords (Wager 1995; Rooney 2005; Vann 2002). In late 1989, the process of Angkor’s inscription on to the World Heritage List began. In a meeting held in Paris on 1 September 1989, between the Director-General of UNESCO and His Royal Highness Prince Sihanouk on behalf of the United Nations-recognized Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea, a request for international assistance in conserving and preserving the monuments of Angkor was made (UNESCO 1993; Wager 1995). Angkor was initially placed on the World Heritage-In-Danger list due to the political situation in the country. The In-Danger listing meant that a full listing was conditional upon certain criteria being met; after a number of years the criteria were met and the property was removed from the In-Danger list and placed on the full World Heritage List (Gillespie 2010). In order to understand the place of Angkor in the hearts and minds of the Khmer people, and to reiterate its importance in the social fabric of Cambodian society, the chapter now turns to what makes Angkor so special.Angkor past and present

The temples and structures of Angkor are a legacy of the great Khmer Empire, which ruled through a vast area of mainland Southeast Asia between the eighth and fifteenth centuries CE . Angkor-period remains are scattered over a large area and recent remote-sensing investigations reveal an urban landscape of unexpected size and complexity (Evans et al. 2007; Evans et al. 2013). Angkor is now understood to be have been a vast, low density urban complex covering around 1000 km2 , with an extensive high-density core and a sprawling low-density fringe. The architectural and infrastructural remains are the product of hundreds of years of iterative development and renovation by successive Khmer kings, producing an extraordinarily rich and complex cultural landscape.Today, the archaeological complex of Angkor covers a vast area – the World Heritage site alone covers an area in excess of 400 km2 - eBook - ePub

- Peter Church(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Jayavarman II built several such temples at widely spaced sites in what is now Cambodia. For the next four centuries his successors would build their temple‐mausoleums, the successive foci of South‐East Asia's greatest state until the 13th century. The temples of the Angkor region are still South‐East Asia's most imposing historical remains.From the mid‐ninth century, Angkor's heartland became the region along the northern end of the Tonle Sap, near the modern city of Siem Reap. The Tonle Sap (“great lake”) floods each year, fed by the rushing waters of the Mekong. Angkor's rulers and people gradually built a system of reservoirs and canals to control the inundation and provide year‐round water for multiple rice harvests. The system eventually watered an area of about 5.5 million hectares and supported a large population. A bureaucracy of regional magnates and officials harnessed the labour and product of this population for the king's projects and their own—temple‐building, the lavish decoration and upkeep of temples and palaces, the expansion and maintenance of the irrigation works, trade with merchants sailing up the Mekong/Tonle Sap, and warfare.The degree of power personally exercised by the “god‐kings” remains uncertain, despite the rich information about Angkor provided by temple inscriptions and bas‐reliefs. Modern scholars' characterizations of Angkor's rulers vary from Stalinesque tyrants to ceremonial figureheads always in danger from court rivalries and regional challenges. Two men of immensely strong personality stand out from the long line of monarchs—Suryavarman II (reigned 1113–1150) and Jayavarman VII (reigned 1181–c.1219). The former took the empire which Angkor had been developing to its greatest extent. Under him it encompassed much of modern Thailand and Laos, Cambodia, and southern Vietnam. For a time he also held the territory of Champa, today's central Vietnam. Appropriately, Suryavarman II initiated the construction of Angkor Wat, sometimes described as the largest religious building in the world, and Angkor's best known monument. - eBook - ePub

- Tim Winter(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

5 Angkor in the frameSo far the evolution of Angkor as a site of tourism performance has been discussed in relation to broader political and economic processes, infrastructure resources or policy developments. Up until this point we have yet to hear the voice of the tourist. The following two chapters fill this void by addressing Angkor as a site of consumption. Divided into two parts, international and domestic, this chapter weaves together cultural artifacts – spanning airline adverts to guidebooks, paintings to themed hotels – with the narratives and practices of visitors to reveal how distinct, and politically charged, formations of an Angkorean culture, landscape, and history circulate within the context of tourism today.The chapter opens with ‘The Eighth Wonder of the World’ exploring the relationship between a vision of an ‘ancient’ Angkor and its representation as a World Heritage Site. It is argued that the tourism industry principally presents Angkor as the legacy of a classical civilization, and that such a vision reinforces, and is reinforced by, the site’s recent designation as world heritage. Through an examination of ‘world heritage tours’ it is also suggested that a new cultural topography has been inscribed through Angkor’s inclusion in itineraries traversing the ‘cultural highlights’ of Southeast Asia. The idea of Angkor as a classical civilization has also been accompanied by a second, equally dominant, framing: that of the ruin. In ‘The Mother of All Lost Cities’ representations and narratives of Angkor as a set of ‘romantic’ ruins reclaimed from the jungle are discussed. In addition to once again tracing the lineage of such a construction back to the colonial framings outlined earlier, it will be seen that Angkor, as ruin, serves as a metonym of nostalgia for a bygone and romanticized Indochina.The final section examining non-Cambodian tourists, entitled ‘I Survived Cambodia’, turns to imaginings and representations of the country as a whole. It will be seen that the overwhelming image of Cambodia presented in guidebooks, travel literature and by tourists themselves is one of danger, landmines, and political turmoil. This is an image that both repels and attracts. For some it is just another ‘war-torn, dusty Asian country’ that holds little interest; for others it is a luring frontier of discovery, risk, and danger tourism. Either way, tourists struggle to connect a glorious and ancient Angkor with a war-torn and contemporary Cambodia. Continually pulling in the analysis of the previous chapter, these three sections illustrate how Angkor has been transformed into a spatial and cultural enclave within a context of international tourism; a landscape socio-historically disembedded from its Cambodian context. - eBook - ePub

Architectural Conservation in Asia

National Experiences and Practice

- John H. Stubbs, Robert G. Thomson(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The vast expanse of the greater Angkor area, which is generously graced with a rich variety of remarkably well-preserved architectural forms representing nearly 500 years of stylistic evolutions, gives credence to its description by historian Arnold J. Toynbee: “Angkor is not orchestral; it is monumental.” 6 Given today’s perspectives on cultural heritage, it’s actually both. An inscription at the intermediate gallery of Angkor Wat temple’s east entrance provides evidence of the extensive restoration done during the sixteenth century by King Ang Chan of the key temple sites of Angkor Wat and at Phnom Bakheng, the state temple of the nearby earlier capital Yasodharapura that was built by Yasovarman I. Touchingly, it was dedicated by his mother in the seventeenth century: “[He] restored the holy city of Yasodharapura, long deserted, and rendered it superb and charming … ornamented with shining gold, palaces glittering with precious stones, like the palace of Indra on earth.” 7 Historical evidence of this initiative can be seen today in the restorations of portals in the upper reaches of Angkor Wat and in the sixteenth century restorations of a statue of Vishnu in Angkor Wat’s west gopura (entrance building), which is currently considered to be the most famous statue in Khmer art. 8 Figure 8.5 Restorations of destroyed portals in the upper reaches of the Angkor Wat temple date from an attempted revival of Angkor under King Ang Chan in the sixteenth century CE - eBook - ePub

- (Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

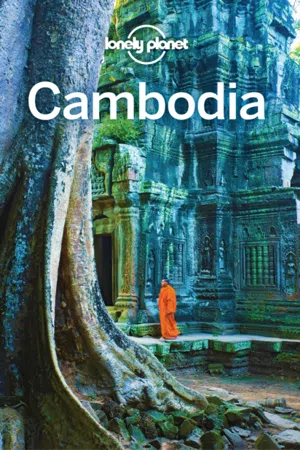

- Lonely Planet(Publisher)

A number of scholars have argued that decline was already on the horizon at the time Angkor Wat was built, when the Angkorian empire was at the height of its remarkable productivity. There are indications that the irrigation network was overworked and slowly starting to silt up due to the massive deforestation that had taken place in the heavily populated areas to the north and east of Angkor. This was exacerbated by prolonged periods of drought in the 14th century, which was more recently discovered through the advanced analysis of dendrochronology, or the study of tree rings, in the Angkor area.Massive construction projects such as Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom no doubt put an enormous strain on the royal coffers and on thousands of slaves and common people who subsidised them in hard labour and taxes. Following the reign of Jayavarman VII, temple construction effectively ground to a halt, in large part because Jayavarman VII’s public works had quarried local sandstone into oblivion and left the population exhausted.Another challenge for the later kings was religious conflict and internecine rivalries. The state religion changed back and forth several times during the twilight years of the empire, and kings spent more time engaged in iconoclasm, defacing the temples of their predecessors, than building monuments to their own achievements. From time to time this boiled over into civil war.Angkor was losing control over the peripheries of its empire. At the same time, the Thais were ascendant, having migrated south from Yunnan, China, to escape Kublai Khan and his Mongol hordes. The Thais, first from Sukothai, later Ayuthaya, grew in strength and made repeated incursions into Angkor before finally sacking the city in 1431 and making off with thousands of intellectuals, artisans and dancers from the royal court. During this period, perhaps drawn by the opportunities for sea trade with China and fearful of the increasingly bellicose Thais, the Khmer elite began to migrate to the Phnom Penh area. The capital shifted several times over the centuries but eventually settled in present-day Phnom Penh.

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.