History

Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, fought in April 1862 during the American Civil War, was a significant and bloody engagement between Union and Confederate forces. The battle resulted in a Union victory, but at a high cost in casualties for both sides. It marked a turning point in the war, demonstrating the scale and ferocity of the conflict.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

6 Key excerpts on "Battle of Shiloh"

- eBook - ePub

Shiloh

Conquer or Perish

- Timothy B. Smith(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Press of Kansas(Publisher)

5T he terrain on which the Federal army camped was perfect for their purposes of a staging area, and that was all they ever intended it to be. Unknown to them, it would also eventually be where a major battle was fought, and in that realm, it served the Federals even better. One Union soldier went so far as to write, “Nature had done her share in the making of an almost impregnable position,” and a Federal colonel similarly wrote, “You might search the world over and not find a more advantageous field of battle.” Federal commanders did not know it quite in those terms yet, but this staging area and campground provided them very defensible terrain. William Preston Johnston went so far as to describe the ailing Smith’s decision to place the army on the west bank of the river as “the dying gift of the soldierly C. F. Smith to his cause.”6Any understanding of the Battle of Shiloh has to start with an understanding of the terrain on which it was fought. The dominant terrain feature was the Tennessee River. The river was 300 to 400 yards wide at Pittsburg—far too broad to ford in such a rainy spring as this one. While at times fordable in the dry summers, the river formed a wide eastern boundary to what would become the Shiloh battlefield. Yet lesser watercourses flowing into the river played a far greater role than the Tennessee in shaping the battlefield. Two major creeks flowed into the Tennessee River on either side of Pittsburg Landing, setting the basic parameters of the staging area. A wide—and at flood stage daunting—Snake Creek, with steep banks along the high ground nearer Pittsburg, emptied into the river half a mile north of the landing. Water frequently backed up into the creek; it could only be crossed at bridges, and oftentimes in the spring not even there. Snake Creek flowed in a large loop at the northern end of the campsite, but its major tributary actually had more of an effect on the western boundary. Owl Creek flowed from southwest to northeast, meeting Snake Creek just as it began its giant loop to the north. Owl Creek was similarly substantial so that it could not be forded just anywhere, although because it was farther up the watershed it was not as affected by the river’s rises and falls. The swampy bottoms of Snake and Owl creeks thus formed the northern and western boundaries of the Federal staging area. Similarly, several miles to the south, Lick Creek formed the southeastern boundary, flowing into the Tennessee River some two miles south of Pittsburg Landing. Like Snake Creek, Lick was deep and wide and generally flowed parallel to Owl Creek, from southwest to northeast. It was also susceptible to the river’s backwater, especially in the spring, making it similarly difficult to cross except by bridge.7 - eBook - ePub

The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant

The Complete Annotated Edition

- Ulysses S. Grant(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

The description of the Battle of Shiloh given by Colonel Wm. Preston Johnston is very graphic and well told. The reader will imagine that he can see each blow struck, a demoralized and broken mob of Union soldiers, each blow sending the enemy more demoralized than ever towards the Tennessee River, which was a little more than two miles away at the beginning of the onset. If the reader does not stop to inquire why, with such Confederate success for more than twelve hours of hard fighting, the National troops were not all killed, captured or driven into the river, he will regard the pen picture as perfect. But I witnessed the fight from the National side from eight o’clock in the morning until night closed the contest. I see but little in the description that I can recognize. The Confederate troops fought well and deserve commendation enough for their bravery and endurance on the 6th of April, without detracting from their antagonists or claiming anything more than their just dues.The reports of the enemy show that their condition at the end of the first day was deplorable; their losses in killed and wounded had been very heavy, and their stragglers had been quite as numerous as on the National side, with the difference that those of the enemy left the field entirely and were not brought back to their respective commands for many days.17 On the Union side but few of the stragglers fell back further than the landing on the river, and many of these were in line for duty on the second day. The admissions of the highest Confederate officers engaged at Shiloh make the claim of a victory for them absurd. The victory was not to either party until the battle was over. It was then a Union victory, in which the Armies of the Tennessee and the Ohio both participated. But the Army of the Tennessee fought the entire rebel army on the 6th and held it at bay until near night; and night alone closed the conflict and not the three regiments of Nelson’s division.18 - eBook - ePub

Civil War Places

Seeing the Conflict through the Eyes of Its Leading Historians

- Gary W. Gallagher, J. Matthew Gallman(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- The University of North Carolina Press(Publisher)

I BATTLEFIELDSPLACES OF FIGHTING

Passage contains an image

1 THE CHURCH IN THE MAELSTROM

STEPHEN BERRY

Interior of Shiloh Church, Tennessee (Photograph by Will Gallagher)But go ye now unto my place which [was] in Shiloh, where I set my name at the first, and see what I did to it for the wickedness of my people .—Jeremiah 7:12Before it named a battle and a battlefield, Shiloh Church was the center of a community. Erected in 1851, the humble church sat at a small crossroads in heavily wooded tableland three miles west of the bend in the Tennessee River where waters that have run all the way from the Appalachians cease their westward track across the top of Alabama and plunge due north, back into Tennessee and all the way to the Ohio River. The congregants of Shiloh Church were mostly Methodist, but their meetinghouse was more than a place of worship; it was their school and their muster grounds, the place where they went to picnic and play, gossip and talk politics. What they couldn’t get at the church, they got at the only other public facility within walking distance: Pitts Thacker’s grog shop located just up the road at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee. Prior to its demolition, then, Shiloh may not have been a town, but it did possess the minimal qualifications of an American community: a church and a bar.Growing up around Shiloh Church, Elsie Duncan remembered her community as an idyll in the woods. The forest was beautiful, she said, “with every kind of oak, maple and birch, [with] fruit trees and berry bushes and a spring-fed pond with water lilies blooming white.” As the nine-year-old daughter of Shiloh’s circuit-riding minister, Elsie knew the woods well. On the morning of the battle, she remembered that “the sun was shining, birds were singing, and the air was soft and sweet. I sat down under a holly-hock bush which was full of pink blossoms and watched the bees gathering honey.”1Disembarking at Pittsburg Landing, many of Ulysses S. Grant’s soldiers saw not an idyll but a muddy, squalid waste, which, in fairness, Shiloh also was. (Even one local historian damningly noted that “a more unprofitable spot of land, perhaps, could not have been selected … for a battleground … with less loss to the country.”) “Pittsburg Landing … excited nothing but disgust and ridicule,” said one Federal. “A small, dilapidated storehouse was the only building there.” The surrounding area was “an uninteresting tract of country, cut up by rough ravines and ridges, [where] here and there an irregular field and rude cabin indicated a puny effort at agriculture.”2 - eBook - ePub

The Woman in Battle

A Narrative of the Exploits, Adventures, and Travels of Madame Loreta Janeta Velazquez, Otherwise Known as Lieutenant Harry T. Buford, Confederate States Army

- Janeta Velazquez, C. J. Worthington(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

[Page 200] CHAPTER XVII.THE Battle of Shiloh.

A Surprise upon the Federal Army at Pittsburg Landing arranged.—A brilliant Victory expected.—I start for the Front, and encamp for the Night at Monterey.—My Slumbers disturbed by a Rain-storm.—I find General Hardee near Shiloh Church, and ask Permission to take a Hand in the Fight.—The Opening of the Battle.—Complete Surprise of the Federals.—I see my Arkansas Company, and join it.—A Lieutenant being killed, I take his Place, amid a hearty Cheer from the Men.—A Secret revealed.—I fight through the Battle under the Command of my Lover.—Furious Assaults on the Enemy’s Lines.—The Bullets fly thick and fast.—General Albert Sydney Johnston killed.—End of the first Day’s Battle, and Victory for the Confederates.—Beauregard’s Error in not pursuing his Advantage.—I slip through the Lines after Dark, and watch what is going on at Pittsburg Landing.—The Gunboats open Fire.—Unpleasant Effect of Shells from big Guns.—Utter Demoralization of the Federals.—Arrival of Buell with Re-enforcements.—General Grant and another general Officer pass near me in a Boat, and I am tempted to take a Shot at them. —I return to Camp, and wish to report what I had seen to General Bureaugard, but am dissuaded from doing so by my Captain.—Uneasy Slumbers.—Commencement of the second Day’s Fight.—The Confederates unable to contend with the Odds against them.—A lost Opportunity.—The Confederates defeated, and compelled to retire from the Field.—I remain in the Woods near the Battle-field all Night.FORT DONELSON was to be avenged. After the capture of that position, the Federals had swept in triumph through Tennessee, the Confederates having been compelled to abandon their lines in that state and in Kentucky, and to seek a new base of operations farther south. The Federals were now concentrating in great force at Pittsburg Landing, on the Tennessee River, their immediate object of attack evidently being Corinth, and General Albert Sydney Johnston, who was in command of the entire Confederate army, resolved upon striking a vigorous blow at once, with a view of turning the tide of victory in our favor before the enemy were assembled [Page 201] in such strength as to make it imperative for us to act upon the defensive, and to fight behind our intrenchments. The experiences of more than one well-fought field had shown how well nigh irresistible the Confederate soldiers were in making an attack, and the general knew that it would be necessary for him to be the assailant, if he expected to get all the work out of his men they were able to do. - eBook - ePub

- Hal Jespersen, James R. Knight, Dana Lombardy(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Lombardy Studios(Publisher)

Battle of Shiloh

April 6, 1862: 5 a.m. to 9 a.m.

“Tomorrow ... we will water our horses in the Tennessee River.”General Albert Sidney Johnston, the night before Shiloh1A fter two nights of rain, Sunday morning, April 6 dawned cool and clear. Johnston’s army was finally in position to attack, but the configuration changed. In a telegram to President Davis, Johnston explained that his formation would be one line, with Polk on the left, Hardee in the center, and Bragg on the right.2 This morning, however, his subordinate commands were stacked narrower and deeper. Hardee’s corps was the front line, Bragg’s corps a second line, parallel to Hardee but about 800 yards to the rear, followed by Polk’s corps and the reserve corps under Breckinridge in column further back.3 Johnston’s basic strategy, however, was unchanged—to sweep around the Federal left, cut them off from Pittsburg Landing, and pin the enemy against Owl Creek.The Federal forces were not taken completely by surprise. There was increased skirmishing during the last few days, mainly near Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 5th Division, and he was aware of Confederate forces of possibly regimental strength within a couple of miles to his front. He did not, however, consider them much of a threat. He sent the following note to Grant about 12 hours before the battle:The enemy is saucy, but got the worst of it yesterday, and will not press our pickets far... I do not apprehend anything like an attack on our position.4Neither Sherman nor any of the other Federal commanders had any idea that the entire Confederate army was almost within cannon shot on Saturday night, but one of them was about to find out.About 3 a.m. on Sunday morning, Col. Everett Peabody, commander of a brigade in Brig. Gen Benjamin M. Prentiss’s division, sent out a large patrol led by Major James Powell.5 Less than two miles out, Powell’s Missouri and Michigan men flushed a few Confederate riders and then, just after 5 a.m., they ran into Maj. Aaron B. Hardcastle’s 3rd - eBook - ePub

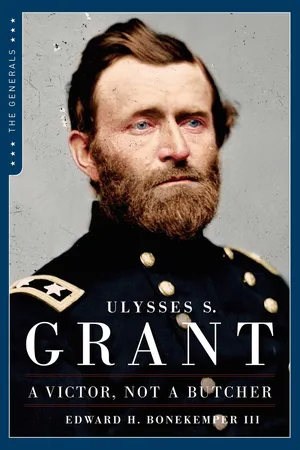

Ulysses S. Grant: A Victor, Not a Butcher

The Military Genius of the Man Who Won the Civil War

- Edward H. Bonekemper(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Regnery History(Publisher)

5 dp n="59" folio="40" ?Meanwhile, the Confederates were planning an offensive of their own. General Albert Sidney Johnston, a man senior to Robert E. Lee and all other Confederate generals except one, was assembling an impressive force at Corinth. He was gathering troops from across the South, including the Gulf Coast, the southeastern Atlantic Coast (including Beauregard and many troops from Charleston, South Carolina), and the Mississippi Valley (including Polk’s forces that had abandoned Columbus, Kentucky). On April 2, Johnston began moving his 44,000 troops the twenty miles toward Pittsburg Landing. In those first few days of April, Johnston’s cavalry sporadically encountered Grant’s pickets, but this was not enough to lead Grant to expect a Confederate offensive. One day before this surprise attack was to occur, still unaware of Johnston’s plan, Grant told a fellow officer, “There will be no fight at Pittsburg Landing; we will have to go to Corinth, where the rebels are fortified.” In his memoirs, he later explained: “The fact is, I regarded the campaign we were engaged in as an offensive one and had no idea that the enemy would leave strong entrenchments to take the initiative when he knew he would be attacked where he was if he remained.”6The frequency of skirmishes continued to increase, and on April 4 Grant was injured as he rode back to his headquarters in the dark. He had been meeting with officers from the front lines when his horse fell on his leg; he was unable to walk without crutches for two or three days. At that time, Grant was spending his nights downriver from Crump’s and Pittsburg Landings at Savannah, where Buell’s Army was expected to arrive. On April 5, Brigadier General William (“Bull”) Nelson and the lead division of Buell’s Army arrived at Savannah. Grant ordered Nelson to proceed down the east bank of the Tennessee so that he could be ferried across to Crump’s or Pittsburg Landing.7

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.