History

Decline Of Empires

The decline of empires refers to the gradual weakening and eventual collapse of powerful political entities. This process is often marked by internal strife, external pressures, economic challenges, and shifts in power dynamics. The decline of empires has been a recurring theme throughout history, with examples including the fall of the Roman Empire, the decline of the Ottoman Empire, and the dissolution of the British Empire.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

3 Key excerpts on "Decline Of Empires"

- eBook - ePub

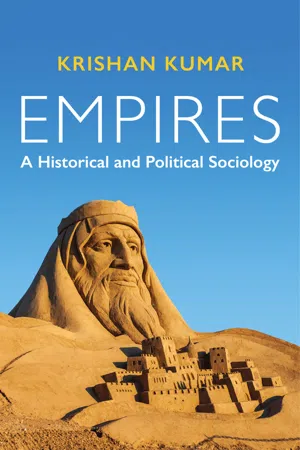

Empires

A Historical and Political Sociology

- Krishan Kumar(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Polity(Publisher)

It is clear in any case that the post-1945 wave of decolonization, rapid and remarkable as it was, was not the end of the story of empire. The European empires may have gone, at least formally. But not only did that not mean that they did not continue to exercise a formidable degree of informal influence and control over their erstwhile colonies – in many cases, with the willing consent of at least the elites of the newly independent states. There was also the continued existence of the American and Soviet empires, much as they disowned the name of empire. They dominated the international scene after 1945, as global powers that acted frequently as the European empires of old. The Europeans, for their part, came together in a “European Union” that was a kind of substitute for their lost empires, and which in the eyes of some actually had the characteristics of some of the older forms of empire.Empire had, and has, an after-life that continues to affect both the metropolitan societies and the territories over which they formerly ruled. It is to that continuing story of empire that we must now, in conclusion, turn.Notes

- 1. For the role of apocalyptic Christian thought in communicating the “sense of an ending” in a wide variety of contexts in European societies, see Kermode (2000). See also, for the European experience of decline in social and economic terms, Thompson (1998).

- 2. For edited collections and studies of the decline and fall of empires, ancient and modern, see Eisenstadt (1967); Cipolla (1970); Kennedy (1989); Barkey and von Hagen (1997); Dawisha and Parrott (1997); Brix et al. (2001).

- 3. “The collapse of Rome,” says Michael Mann, “is the greatest tragic and moral story of Western culture” (Mann 1986: 283; and see 283–98 for his interesting account of the fall).

- 4. A clear statement of the inevitability thesis is Motyl (2001). See also Parsons (2010).

- 5. Further, as Alexander Motyl says, “if overreach gets empires into trouble after several hundred years of plenitude, surely it cannot be all that alarming” (Motyl 1999: 140).

- 6.

- eBook - ePub

Great Powers and the Quest for Hegemony

The World Order since 1500

- Jeremy Black(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

8 The fall of empires, 1943–91A series of empires fell in this period, although the processes involved were very different. First, Allied victory in the Second World War led to the destruction of the Nazi and Japanese empires in 1944–5. This great-power conflict was followed by the passing of the European colonial empires, that of the Dutch in the East Indies followed by the end of the Belgian, British, French and Portuguese empires: a process completed in 1975 when Portugal granted independence to its colonies. In the late 1980s, increasingly serious and insoluble internal political and economic strains and dissidence led to the collapse of the Soviet empire (and Communist system) in Eastern Europe, which was followed, in the early 1990s, by that of the Soviet Union itself.Very different factors were at work in these various processes, with the collapse of the Soviet empire involving very little fighting. The very diversity presents obvious problems of classification and definition: alongside force and organizational factors, it is pertinent to note the role of political factors in encouraging the spread of Western power and, conversely, of these political factors in undermining it. The latter encourages a focus on the role of ideology and belief, in both periphery and metropole, in making rule by others seem aberrant rather than normative. This is crucial to the contrast between growing technological prowess on the part of the major powers, and the more limited role they sought, and success they enjoyed, as imperial powers. The most successful—China in Tibet and Xinjiang—also owed its success to demographic weight and the opportunities it created for settlement.It is, therefore, appropriate to note that other factors have to be assessed alongside technology. Focusing solely on the latter, superiority in forms of military technology and military—industrial complexes underwrote Western capability in naval and air power, where their effect was fundamental; but precisely the same forms of superiority in technology and industry had a far smaller impact so far as land power goes, certainly insofar as asymmetrical conflict was concerned. A fairly similar pattern, of greater relative power at sea and in the air than on land, is emerging with the so-called Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) today, although the latter also gives Western armies far more power on the conventional battlefield. Nevertheless, dethroning technology from its central role in military capability, let alone the causes of success, helps explain why the Western powers were unable to prevail in many of the conflicts in the Third World. Turning back, this demonstrates, more generally, the need to understand the role of cultural assumptions, and political activity, in the analysis of military history and international relations. - eBook - ePub

America As Empire

Global Leader or Rogue Power?

- James Garrison(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Berrett-Koehler Publishers(Publisher)

The Ming dynasty in China grew from around 1350 to around 1450 and then declined over the next two centuries. The Ottoman Empire grew from the 1350s to the 1550s, then remained at its zenith for a full three hundred years before declining during the later part of the 1800s, finally succumbing to the European powers in World War I. The British and the French empires expanded dramatically from 1750 to 1800, reached their peak by 1900, and then lost virtually everything in the aftermath of World War II. 116 THE RISE AND FALL OF EMPIRES Imperial beginnings are marked by decisive leadership, clear objectives, the willingness to use force to gain strategic ends, and an esprit de corps that motivates the dominant nation to spill over its borders for land, resources, and control. The conquests of Alexander the Great provide the classic example of an empire formed by the charisma of a military leader; Alexander swept out of Greece and over Persia at the age of eighteen by the sheer force of personality and military genius. Genghis Khan is another example, sweeping out of Mongolia in 1206 to establish the largest empire in history, which at its zenith covered two-thirds of the Eurasian landmass. Military historians consider the Khan the father of modern warfare and one of the greatest military tacticians in the history of war. Napoleon provides a more contemporary example of an emperor who extended territory by a combination of military brilliance and the esprit de corps of an army, in his case inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution. Expanding empires generally possess superior military technology, greater social differentiation, and deeper institutional cohesiveness than the nations they conquer. In the case of Alexander, it was his refinement of the phalanx and tactical maneuvering. With Genghis Khan, it was his extraordinary use of the horse

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.