History

Medieval Punishments

Medieval punishments were often brutal and aimed at deterring crime through fear and pain. Common forms of punishment included flogging, branding, mutilation, and public executions such as hanging, beheading, or burning at the stake. These punishments were often carried out in public as a means of both punishing the individual and sending a message to the community.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

9 Key excerpts on "Medieval Punishments"

- eBook - ePub

A Social History of Disability in the Middle Ages

Cultural Considerations of Physical Impairment

- Irina Metzler(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

10It is certainly the case that during the later Middle Ages corporal punishments were coming to be favoured over other punitive measures, such as monetary fines or imprisonment. For instance, around 1500, within a two-week-stretch alone in Nuremberg two men were hung, a charcoal burner was beheaded, an eighty-year-old peasant had both eyes gouged out and a maid who had “stolen much” (vil gestoln) had her ears cut off.11 Judicial practices perhaps echoed or reflected wider social mentalities, so that:one of the defining features of this Christianized, late medieval ‘paradigm’ of punitive justice, namely, a distinctive mode of judicial spectatorship, fretted with the visual habits and devotional attitudes unique to this period.12Hints are occasionally provided by the documentary record that mutilating punishments were not necessarily carried out but instead commuted to fines.13 From a study of the archives of Bruges in the fifteenth century, Malcolm Letts had drawn the conclusion that:a large number of offences, which we might expect to be punished by loss of liberty or by mutilation, were dealt with at Bruges by fines only. Fines were imposed for larceny, housebreaking and burglary, threats to murder, wounding, violent and aggravated assaults, adultery, forcible entry, common theft, for wapeldrink, a curious ducking offence which was regarded very seriously in Flanders at this time, and for various offences against the peace, which would seem in any age to have merited more serious treatment.14More recently, according to Robert Mills, it seems, too, that “judicial violence was exercised selectively and acquittals and reduction of sentences were often the order of the day”15 across late medieval Europe. Social historian John Bellamy had put forward the argument that physical punishments, such as judicial mutilation or branding, were relatively rare in England in the high Middle Ages, as compared with either the first century after the Norman conquest or with the fifteenth century and following.16 Miri Rubin in turn, however, commented that the study of maiming through judicial punishment and torture was hindered by the paucity of medieval sources.17 The ‘classic’ portrait of the later Middle Ages as especially ‘barbaric’ and full of violence (judicial and otherwise) is derived from the opening chapter—“The Violent Tenor of Life”—of an influential volume originally published in 1919, Huizinga’s The Autumn [Waning] of the Middle Ages.18 - eBook - ePub

Why the Middle Ages Matter

Medieval Light on Modern Injustice

- Celia Chazelle, Simon Doubleday, Felice Lifshitz, Amy G. Remensnyder(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

5Early medieval practices underscore the value of community and reparative justice for responding to nonviolent offenders in cities like Camden and, further, point toward initiatives that could provide similar benefits when dealing with violent offenders. Among the advantages of looking at modern penal policies through the lens of early medieval justice, one is that it reveals the particular importance of family and social networks to community wellbeing.Early Medieval JusticeThe best known medieval European judicial punishments are no doubt the spectacularly dramatic, painful torments seen in Hollywood films and Far Side cartoons: bodies broken on wheels and hanging from public gallows, beheadings, burnings, tortures like the thumbscrew and the rack. Foucault famously begins Discipline and Punish with a lurid account of the torture and drawing and quartering of Damiens, the would-be regicide (king-killer), in Paris in 1757. For Foucault, this scene harked back to a medieval emphasis on punishing the body, an approach to crime for which, he asserts, modernity has substituted the equally coercive punishment of prison. We now realize physical torture is still with us; but most Americans would agree that prisons illustrate our modernity, and most – unlike Foucault – believe these institutions are far more humane than any penalties of the middle ages.Medieval records, however, reveal a more nuanced situation. The majority of the sources for studying medieval penalties date from the twelfth and later centuries. The evidence is sparser for the early middle ages, yet people then, too, were familiar with a host of painful practices. Early medieval lawcodes enjoin execution for offenses ranging from homicide to adultery to relapsing into paganism. Narrative sources tell of kings and aristocrats who condemned enemies to exile or death, and of lords who commanded that dependents be branded, blinded, or lose noses or ears. Courts ordered torture and ordeals – such as trial by fire, where the suspect walked on burning coals, or trial by water where he or she picked an object out of boiling water. Skeletons unearthed from burial grounds show the effects of decapitation, amputation, and limbs bound possibly for hanging.6 Furthermore, while imprisonment was unusual, it was not absent, and again the experience must have been decidedly unpleasant. Nobles who rebelled against kings, priests who disobeyed bishops, and slaves or serfs (people of servile or unfree status) who tried to escape were sometimes confined in monasteries; some religious houses had a special room called a carcer - eBook - ePub

- Graeme Newman(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

6 Punishing CriminalsI have so far concentrated on death and other bloody punishments from the point of view of their sacred origins or their rather narrowly defined use in the service of obedience within family, school, or religion. It is now time to place the use of punishment into a broader political perspective, by analyzing the relationship of punishment to the economic and social structure of society. I will do this very briefly for the period prior to the middle ages, and then concentrate specifically on the development of criminal punishment in English history.1Punishment up to the Middle Ages

If I have given the impression so far that the major forms of punishment in ancient times were those of bloodthirsty physical injury, I must apologize for a little sleight of hand. In proportion to other punishments that we would consider mild today, such as fines or compensations, severe physical punishment was not the most common form used in ancient times. The death penalty, for example, was used rarely in classical Greece, although often pronounced for serious crimes. In Athens the more common punishment was to banish the criminal by the vote of 6,000, and if the criminal refused banishment, then the death penalty followed. Socrates could have elected exile had he wished. This practice was continued on a much greater scale by the Romans, who encouraged those under death sentence to go into voluntary exile. In general, in classical Greece only those criminals caught in flagrante delicto were executed, and this was done on the spot by special commissioners appointed for the purpose.2In classical Rome the death penalty was almost never inflicted,3 although there is some disagreement in the literature as to whether this applied also to slaves. The only crime for which capital punishment was administered arbitrarily was for furtum manifestum, a thief caught in the act, who was executed on the spot, preferably by the accuser. This apparently overzealous punishment is directly related to the central part that the Roman house and family played in Roman law. Free men were certainly rarely executed from second to first centuries B.C.—the height of the Republic. And it was not until A.D. 250 and 257 that the great persecutions of the Christians occurred under the Emperor Valerian, and this again only for a very brief period.4 - eBook - ePub

Crime in Medieval Europe

1200-1550

- Trevor Dean(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

However, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the option often existed to pay a fine instead. 45 The pillory, ladder or stocks was often used for minor offences: the offender was attached to it for a set number of hours on a market day, to the general ridicule of bystanders. In Aberdeen in 1405 a cuckstool was instituted for insults to urban or royal officers: for a first offence, the miscreant was to kiss the stool; for a second, he or she was to be placed on it and defiled with eggs, dung and muck. 46 In France in 1397 the king ordered that for a first offence of blasphemy, the culprit was to stand in the pillory from early morning to mid-afternoon, so that people could throw mud and other filth at them, and then spend a month in prison on bread and water. 47 Monetary penalties The dominant forms of punishment in the Middle Ages were in fact the money fine and banishment or exile, penalties that depleted the convict’s assets or expelled him from the community. This has been amply demonstrated by the French historian Robert Muchembled in his book Le temps des supplices. In contrast to Foucault’s focus on horrific pain, Muchembled shows that ‘judicial fines were at the heart of the system’ in the later Middle Ages. It was not until the sixteenth century that ‘the real period of tortured bodies arrives’, with more and greater ‘punitive festivals, offering to the crowds of spectators a liturgy based on a new sacrality of public power’. Muchembled’s study is limited to the town of Arras and its region in northern France, but as we shall see, his conclusion regarding the role of fines applies more generally to western Europe. From 1400 to 1436 the judicial authorities in Arras, a town of some 14,000 inhabitants, imposed over 1,600 fines, equivalent to one for every seven to ten inhabitants. ‘The effectiveness of the Arras penal system was largely founded on pecuniary penalties.’ The only other major penalty in frequency of incidence was banishment - eBook - ePub

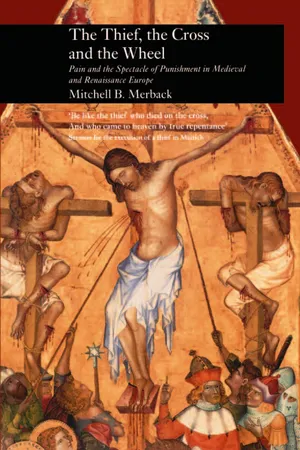

The Thief, the Cross and the Wheel

Pain and the Spectacle of Punishment in Medieval and Renaissance Europe

- Mitchell B. Merback(Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- Reaktion Books(Publisher)

53 Moreover, because whatever may have been originally pagan about these punitive rituals and their requirements had, in the later Middle Ages, already been supplanted by Christian meanings, such theories are of antiquarian rather than critical-historical interest. They obscure more than they explain.Without denying the traditional and folkloric elements in medieval law, we can take a different tack, one which both emphasizes the function of penality in structuring social relationships and is better substantiated by the evidence. Medieval jurisprudence made considerable allowances for the social status of criminals, and consistently distinguished between honourable and disgraceful means of death. The penalties perceived by both élites and popular culture as disgraceful included hanging, breaking with the wheel, burning and every variety of dismemberment. In contrast, decapitation by sword epitomized the honourable death; unlike its vulgar opposites, it brought no stain of infamy on either the condemned or, just as important, his or her family. Petitions for clemency in capital cases very often consisted simply of an attempt to sway judges to commute a dishonouring sentence to decapitation.54 The difference, however, lay only partly in the degree of agony or cruelty involved (though this could never have been far from anyone’s mind). Equally fearsome as excessive pain was the prospect of a punishment that kept the body immobile; vulgar penalties imposed on the victim the added ignominy of going to one’s death bound and helpless. By contrast, decapitation with the sword meant that ‘the condemned remained free and unbound, received the fatal stroke kneeling and thus upright, and had to show enough “honourable” self-control to remain still so that the executioner could deliver an accurate blow’.55 - eBook - ePub

- Barry Godfrey, Paul Lawrence(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Emsley 2005a : 21). The rise of penal welfarism is considered in more detail below but, as stressed in previous chapters, it is important not to see the historical development of the prison and the end of punishments of the body as a smooth continuum of ‘progress’. The changing nature of punishment (and the causes behind these changes), have been the subject of many debates among historians. Before considering these debates, however, it is important first to map out the main trends in punishment. Three interlinked and overlapping forms of punishment must be considered – the death penalty, transportation and the prison.Capital punishment (the death sentence) was still an active penalty for many offences, not just murder, until at least 1830. As discussed in the previous chapter, it was once common for historians to point towards the eighteenth-century Bloody Code (a long series of capital statutes, many of which applied to relatively minor offences) and to assume that punishment in the period was inevitably harsh and unfair. After all, capital offences in the ‘Bloody Code’ included ‘being in the company of gypsies for one month’, ‘vagrancy for soldiers and sailors’ and ‘strong evidence of malice in children aged 7–14 years of age’. However, while there were certainly a lot of executions in the period 1750–1850, many for quite minor offences, the code itself has often been misinterpreted. While voluminous, many of its statutes overlap considerably, merely outlawing the same offence in different areas of the country, for example. Moreover, by the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, around 90 per cent of those condemned to death were receiving pardons or having their sentence commuted to transportation. Juries appear to have been increasingly unwilling to convict on an array of more minor capital charges. As Emsley notes, many in authority began to worry that this tendency was ‘making the judicial system appear an unsustainable lottery’ (Emsley 2005a : 258).However, while there was increasing debate about the efficacy of the death penalty as a deterrent, there is another side to this picture of gradual decline in usage. Gatrell, among others, has noted that there was actually an overall rise in executions during the early part of the nineteenth century, claiming that: - eBook - ePub

Foucault - The Key Ideas

Foucault on philosophy, power, and the sociology of knowledge: a concise introduction

- Paul Oliver(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Teach Yourself(Publisher)

4

The history of punishment

In this chapter you will learn about:- Foucault’s analysis of changes in the types of judicial punishment characteristic of different historical periods

- his analysis of the potential reasons for some of these changes

- his views about the impact of different types of judicial punishment on the individual .

The evolution of systems of punishment

One of Foucault’s most celebrated studies is his exploration of the history of punishment – Surveiller et punir: naissance de la prison (1975; published in English as Discipline and Punish: The birth of the prison in 1977). He starts by looking back to the nature of punishment in the eighteenth century and before. He notes that in this period punishment was characterized by two principal features. First, it was extremely physical rather than psychological. It involved often extreme cruelties and torture, leading to an agonizing death. Secondly, this type of punishment was typically carried out publicly, and indeed appeared to be regarded by the general public as a form of entertainment. The authorities probably conducted such executions in public, partly as an attempt to bring justice into the public domain. People could be perfectly sure that a wrongdoer had received the punishment prescribed by law and would be dissuaded from ever doing something illegal themselves.One may only hypothesize concerning the reasons for people wishing to watch such cruel spectacles. On the one hand, life in the eighteenth century and earlier was harsh, particularly for the social classes who were disadvantaged. Physical punishment may not have been quite as shocking to them as it would be to contemporary society, where we are used to a more ‘civilized’ life. Existence was more precarious because of the prevalence of disease, and people were perhaps more familiar with the imminence of death. Nevertheless, as Foucault pointed out, the prevalent philosophy of punishment entailed inflicting pain on the body. - eBook - ePub

Dead Woman Walking

Executed Women in England and Wales, 1900-55

- Anette Ballinger(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2From Antiquity to Modernity: A Social History of Capital Punishment and GenderThe earliest records of capital punishment taking place in England stem from 450 BC when it was custom to throw the condemned into a quagmire.1 Other early recorded executions include one from the year AD 695 for theft, its purpose being to set an example and discourage others.2 From Anglo-Saxon times onwards the most common method of execution was hanging. The King reserved the right to choose specific forms of death and in addition to the gallows, beheading, burning, drowning, stoning and casting from rocks were also implemented. The Middle Ages saw a steady increase in the numbers of executions carried out each year, with torture accompanying the punishment in the majority of cases. Capital offences included “murder, manslaughter, arson, highway robbery, burglary and larceny,” and in 1382 “the death penalty was extended to heretics under the writ de heretico comburendo …”3 The cheapness of human life is illustrated by a case during the reign of Edward I, when the mayor and the porter of Exeter were executed for failing to shut the city gate in time to prevent the escape of a murderer.4 The sheer numbers put to death is also noteworthy. During the 38-year reign of Henry VIII it has been estimated that 72,000 people were executed.5 Accounting for its larger population this is equivalent to 20,000 people being executed per year in 20th-century Britain.6While men were hanged, drawn and quartered for high treason, women were burned for this crime. Some writers have argued this was done to protect women’s modesty: “For as decency due to the sex forbids the exposing and publicly mangling their bodies, their sentence is to be drawn to the gallows, and there to be burnt alive.”7 Others maintained that:Such judicial ferocity was directed wholly against women offenders. Many complex sociological motives were involved in this inhuman bias, which … was influenced … by the conception of woman as a vessel of sin.8 - eBook - ePub

Criminal Justice Theory

An Introduction

- Roger Hopkins Burke(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

6 Punishment in Modern SocietyThis chapter discusses the philosophy and theory of punishment in modern societies and locates this debate in the context of the four models of criminal justice development that provide the theoretical underpinnings of this text. It is important to remember that all too often punishment is considered to be a distinct and separate entity from the understanding of penology but it is impossible to legitimately understand one without the other, for imprisonment is, next to capital punishment, the harshest and certainly one of the most commonly used sentences. Without the acknowledgement of penal realities, justifications for punishment become mere intellectual debate. Trying to make sense of familiar concepts such as ‘making the punishment fit the crime’, is not strictly a theoretical question and these are not just philosophical matters of concern to academia. These questions have great practical relevance within the criminal justice process generally and the penal system specifically. By bringing the two together, locating penal trends in theory, and grounding theory in policy, the totality becomes greater than the sum of its parts.According to an old Muslim legend, there was once a rich king who left his servant in charge of his kingdom and in receipt of his riches, while he went on a long journey. Upon returning to his kingdom he found to his dismay that his servant had stolen some of his treasures. The rich king took the servant in front of the judge for sentencing. The judge ordered that both the servant and the king should be punished; the servant because he had broken the law, and the king because, by leaving such a great temptation in the hands of a person with so few possessions and possibly weak character (both realities which the king should have been able to assess), the king was in fact causing the man harm (Ellis and Ellis, 1989).

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.