History

Mombasa

Mombasa is a coastal city in Kenya that has a rich history dating back to the 12th century. It was an important trading hub for Arab and Portuguese merchants and was later colonized by the British. Today, Mombasa is a popular tourist destination known for its beaches, historical landmarks, and cultural diversity.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

3 Key excerpts on "Mombasa"

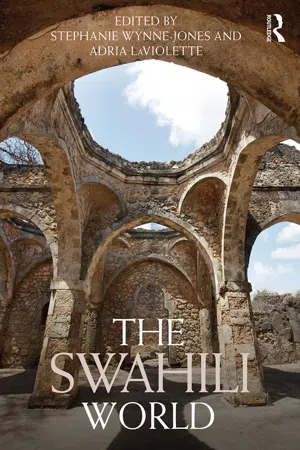

- eBook - ePub

- Stephanie Wynne-Jones, Adria LaViolette(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

To the descendants of freed slaves, the Freretown settlement remains their home and heritage; St Emmanuel Church (completed in 1896), the bell tower and the cemetery are markers of their identity. As places significant to residents and their ancestors, they are depositories for individual and collective memories, symbolic arenas where residents go to gain a physical connection with the past.ConclusionThe strategic position of Mombasa has enabled it to be an important trading centre on the coast for centuries and to play a central role in the international networks of the Indian Ocean. This in turn has contributed to its long and complex history, one that has seen Mombasa as the headquarters of waves of colonial governments. This history has seen terrestrial and maritime Mombasa turned into a ‘memorialscape’ – one that commemorates both good and bad in human nature. As shown above, there are vestiges there that celebrate numerous events, through which multiple histories of Mombasa are simultaneously remembered and forgotten (Macrone 1998; Winter 2005). For instance, while the people of Freretown see St Emmanuel church as the embodiment of their spirituality, Tuaca’s population see Mbaraki Pillar as playing that role. Mombasa’s residents find spiritual nourishment, restoration of their dignity, expression of identity, leadership and achievement, in these places. Even more importantly, the memorialscape of Mombasa has enabled its inhabitants to both place themselves in Mombasa’s cultural and political landscape, and connect to elsewhere in eastern Africa, the western Indian Ocean, and the world.References Abungu G. H. O. 1985. ‘The history of Mombasa and its inhabitants’. Unpublished Papers, National Museums of Kenya, Fort Jesus Museum.Aldrick, J. 1993. ‘The Freretown bell tower at Kengeleni’. Coastweek.Beachey, R. W. 1976. The Slave Trade of Eastern Africa . London: Rex Collings.Berg, F. J. 1968. ‘The Swahili community of Mombasa 1500–1900’. Journal of African History 9 (1): 35–56.Berg, F. J. and Walter, B. J. 1968. ‘Mosques, population and urban development in Mombasa’. Hadith 1: 47–99.Bita, C. 2009. The Intertidal and Foreshore Archaeology of Mombasa Island: An Inventory of Maritime Sites. - eBook - ePub

Shakespeare in Swahililand

Adventures with the Ever-Living Poet

- Edward Wilson-Lee(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- William Collins(Publisher)

As is so often the case, in the rush to record what seemed important at the time much that must have given the fledgling city its flavour was simply treated as unimportant and ephemeral, leaving future ages with a somewhat sterile version of the lives lived by these early settlers. The visitor to today’s Mombasa can still find traces of each of its historic cultures – Arab, Portuguese and Indian, as well as the coastal African tribes – laid out as if an archaeological dig on its side, each stratum a little further from the seaward edge of the estuary island occupied by the town. At that end, overlooking Port Tudor, is the Lusitanian Fort Jesus, built at the behest of Elizabeth I’s chief rival, Philip, where Renaissance sailor graffiti abuts on the markings made by prisoners who were interned here when it was repurposed by the British colonial regime. Working inland from this, there is a slim band of Arabic streets like those in Stone Town, which are kept pristine for the docking tourists who are nowadays unlikely to venture further into the town than this before heading back out to the private beach resorts strung along the coast on either side. Beyond this is a wide swathe of Mombasa which once would have been the preserve of the colonial elite, with the small-gauge local tramway moving past grand institutions, from the Metropole and Castle Royal hotels to the law courts and Mackinnon Market. Now the tramway and the white colonials are gone, and the genteel repose of this part of town buzzes with tuktuk rickshaws moving past Indian dukas, shops where the age-old dried goods in sisal sacks sit next to wall-racks of mobile-phone accessories. At the top of the island, at the point where the railway crosses Kilindini Harbour, the residential districts give way to a modern industrial zone, which looks across a narrow strait to where, atop a teetering landfill, the poorest residents of Mombasa watch the trains enter from the mainland - eBook - ePub

Fortifications, Post-colonialism and Power

Ruins and Imperial Legacies

- João Sarmento(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

It was practically impossible to obtain a precise figure on the number of guided tours that each of them makes per week, a number that obviously varies considerably with the tourism season. Most guides state taking three to four tours per week. This might be the case in the low season, but it is possibly a strong underestimation in the high season. At the same time, prices for guided tours are extremely variable. Guides may charge 200 to 800 shillings (roughly 2 to 8 euros) for a basic one-hour tour in the Fort, and 800 to 2,500 shillings (approximately 8 to 25 euros) for a half-day or even full-day tour of the Fort, old city and other Mombasa attractions. Prices vary according to the duration of the tour, but they also fluctuate according to subjective issues such as the perception of their wealth vis-à-vis their country of origin, party size, bargaining skills, and the way they dress and appear. It is the guides’ perception of what the tourist can pay that is central to this issue. Guides’ common feeling is that this is a highly uncertain business. Not only the guides have to share the tourists among them (they have established a rotation system whereby the guide that arrives puts his name down on a list and has to wait his turn to approach a tourist or group of tourists), but they also feel the negative impact of the increasing number of beach boys and other hustlers and hawkers throughout the country.Mombasa Island is connected to the mainland by several bridges and is part of Mombasa City, the second largest after Nairobi, with well over 600,000 inhabitants. The city is one of the commercial hubs of Kenya, being the most important port in East Africa, and is the centre of a region that is the leading tourist centre is East Africa (in number of hotel beds and other tourist facilities and in number of tourists). But Mombasa is an extremely poor place with very high levels of social deprivation and poverty (Rakodi, Gatabaki-Kamau and Devas 2000). It is estimated that more than a quarter million people live in the city with less than one dollar per day (Kenya Government 2007). Akama and Kieti (2007: 746) have produced a quite important study on the relations between the increasing figures of tourism at a macro level and the strategies that must be put in place in order that local people effectively benefit from this situation, since ‘current forms of tourism development in Kenya have not reduced poverty or contributed to the socio-economic empowerment of local people’. This is a departure point to understand that guides, more than just ‘mediators’ must be entrepreneurs who are required to ‘turn their social relations and narratives into a profitable enterprise’ (Dahles 2002: 784).

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.