History

New Negro Movements

The New Negro Movement, also known as the Harlem Renaissance, was a cultural, social, and artistic explosion that took place in Harlem, New York, during the 1920s. It marked a period of renewed pride and self-expression for African Americans, with a focus on celebrating their heritage and challenging racial stereotypes through literature, music, art, and activism.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

5 Key excerpts on "New Negro Movements"

- eBook - ePub

Black Art

A Cultural History

- Richard J. Powell(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Thames and Hudson Ltd(Publisher)

For composer George Gershwin, publisher Frank Crowninshield, theatrical agent and music publisher Irving Mills, and mobster and nightclub owner Owney Madden, the Harlem Renaissance was, to use American slang, “the hook”: a marketing strategy for New York’s publishers, theater producers, nightclub and cabaret owners, and other business people in the 1920s and 1930s. For black artists like Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, and Ethel Waters, as well as black intellectuals like Locke, Du Bois, James Weldon Johnson, and others, this “Negro Renaissance” was an auspicious moment in American cultural life: African Americans had unprecedented access to, and an active role in, the organizations of the mass media, the venues of mainstream entertainment, and cultural institutions.Finally, for many people this “New Negro” entity was not so much a movement, a moment, or even an actual person, as a mood, or a sentiment in which black culture and its practitioners were seen as a valuable part of the larger cultural scene. In a society that had recently suffered a war of tremendous proportions, and was increasingly changing into an urban, impersonal, and industry-driven machine, black culture was viewed, interchangeably, as life-affirming, a libidinal fix, an antidote for ennui, a sanctuary for the spiritually bereft, a call back to nature, and a subway ticket to modernity. The “New Negro” was the perfect metaphor for this moment of great social rupture because, like a medicine-show elixir, it was perceived as the cure for everything.The term “New Negro,” meaning an enlightened, politically astute African American, sprang from the turn-of-the-century, progressive race rhetoric of Booker T. Washington, of Fannie Barrier Williams, advocate of black women’s rights, and from the illustrations for The Crisis and Voice of the Negro of artist John Henry Adams Jr. As a cultural movement, the term “New Negro” entered into popular usage with two, influential publications in 1925: a special edition of the magazine Survey Graphic , entitled Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro ; and an anthology of essays, short fiction, photographs, drawings, and a short play, entitled The New Negro: An Interpretation - eBook - ePub

Representing the Race

A New Political History of African American Literature

- Gene Andrew Jarrett(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

3New Negro Politics from Reconstruction to the Harlem RenaissanceFrom Reconstruction to the Harlem Renaissance, the symbolic transition of the “Negro” from “Old” to “New” is one of the more compelling stories of the competition of ideological scripts, especially as they pertain to racial representation, in the United States.1 In 1923, the Reverend Reverdy C. Ransom wrote a poem, “The New Negro,” capturing the trope of the New Negro in all its complexity and optimism:Rough hewn from the jungle and the desert’s sands,Slavery was the chisel that fashioned him to form,And gave him all the arts and sciences had won.The lyncher, mob, and stake have been his emery wheel,TO MAKE A POLISHED MAN of strength and power.In him, the latest birth of freedom,God hath again made all things new.Europe and Asia with ebbing tides recede,America’s unfinished arch of freedom waits,Till he, the corner stone of strengthIs lifted into place and power. Behold him! dauntless and unafraid he stands.He comes with laden arms,Bearing rich gifts to science, religion, poetry and song.2Many intellectuals and scholars specializing in nineteenth- or twentieth-century African American literature have told this story, or some variation or part thereof, about New Negro politics, or the way that intellectual culture, in collaboration with formal politics, has helped to “lift” Negroes into the “place and power” that they, as human citizens, rightly deserved.3 New Negro politics accounts for a cultural formation that sought to overcome the prevailing theme, in more mainstream culture, that African Americans were inferior and unassimilable in American “civilization.” Manifest in contexts of literature—as well as in those of drama, illustrations, and speeches—New Negro politics sought to prove that African Americans, then described as a race, could be uplifted in moral, educational, and cultural ways. The proof lay in the images of uplifted African Americans that permeated African American intellectual culture. The feature was a reincarnation of the political rhetoric of miniature portraiture in early America. The literary historian Eric Slauter states that “certain aesthetic assumptions about likeness, resemblance, and form structured American political thought at its foundational moment.”4 - eBook - ePub

- Gene Andrew Jarrett(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Hurston’s travel narrative makes abundantly clear the ways in which the New Negro abroad was as much an American as an African American, the former identity coming more into relief against the backdrop of black worlds away from home. The period between the wars saw the emergence of an increasingly self-conscious New World Negro, who could use the language of revolutionary radicalism and national self-determination alike to shape a new sense of his own black political identity. Alongside political awareness came an artistic appreciation of the histories and cultural forms blacks in the New World potentially shared with each other, politics and culture combining to create the shadowy sense of a unified black, diasporic, imaginary. This black worldliness represented a shared set of beliefs and mindsets that provided the New Negro with counter-cultural tools to navigate the events of the early twentieth century. But the fractures and differences within New World blackness also came along for the ride, issues concerning color, gender, and sexuality adding nuance and complexity to the African American notion of a color line. Abroad, black double consciousness was tripled by the salient economic distinctions between blacks across the developed and underdeveloped worlds. Nevertheless, in his and her travels at the beginning of the twentieth century, the New Negro traced the contours of a globalizing black world whose variegated cultural, political, and social features still interact dynamically today.BibliographyAllen, Ernest, Jr. “The New Negro: Explorations in Identity and Social Consciousness, 1910–1922.” In 1915, The Cultural Moment: The New Politics, the New Woman, the New Psychology, the New Art, and the New Theater in America . Ed. Adele Heller and Lois Rudnick. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991. 48–68.Carby, Hazel V. “Proletarian or Revolutionary Literature: C.L.R. James and the Politics of the Trinidadian Renaissance.” South Atlantic Quarterly 87 (1988): 39–52.Césaire, Aimé. “Notes on a Return to the Native Land.” In The Negritude Poets . Ed. Ellen Conroy Kennedy. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1989. 66–79.Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk - eBook - ePub

Deans and Truants

Race and Realism in African American Literature

- Gene Andrew Jarrett(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- University of Pennsylvania Press(Publisher)

We believe that it is too early for such a call. We want to build, if possible, a Megro peoples’ movement in writing. A more explicit statement will be forthcoming in the first issue of New Challenge. I do hope you will feel free to enter the ring with both hands loaded when you review MacKay. Since you know that Harlem School so thoroughly, we felt that you were the only possible person to handle such a book” (italics mine). 1 The social, economic, political, intellectual, and ideological backdrop of black culture in the 1930s provides the context for the lore cycle of racial realism in Wright’s “Negro peoples’ movement in writing.” Calling this movement the cultural representation of “New Negro radicalism”—a term Barbara Foley similarly employs as the inverse of “Harlem Renaissance culturalism”—implies that the term “New Negro” remained in discursive currency in Wright’s work and elsewhere in black intellectual society and culture. 2 The fact that Wright’s literary contemporaries, as well as subsequent writers and scholars, characterized him as a “New Negro” should compel us to take the words of James Edward Smethurst seriously, that we should avoid “obliterating the 1930s as a period of black literary production distinct from that of the New Negro Renaissance, a distinction that many writers and readers of the era certainly felt.” 3 Indeed, in 1939, Locke, perhaps mindful of Wright’s rise to prominence, posed a question to the readers of Opportunity magazine: “Do we confront today on the cultural front another Negro, either a newer Negro or a maturer ‘New Negro’?” 4 Twelve years later, James Baldwin answered Locke’s question when he noted that, “[i]n the thirties, swallowing Marx whole, we discovered the Worker and realized. . . that the aims of the Worker and the Negro were one. This theorem. . . became, nevertheless, one of the slogans of the ‘class struggle’ and the gospel of the New Negro - eBook - ePub

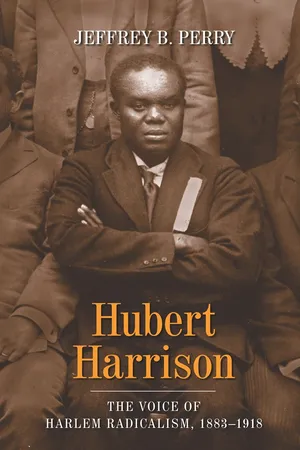

Hubert Harrison

The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918

- Jeffrey B Perry(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

PART 3 The “New Negro Movement”Passage contains an image CHAPTER 9 Focus on HarlemThe Birth of the “New Negro Movement” (1915–1917)

Between 1915 and 1917 Harrison’s indoor and outdoor lectures increasingly focused on the racial aspects of the war. He was encouraged to speak more in Harlem, and he wrote several important theater reviews that helped him to further analyze the “psychology of the Negro.”1 By late 1916 and early 1917 his new focus was clear, and his militant, race conscious lectures at The “Temple of Truth” would signal the dawn of a new era—the birth of “The New Negro Manhood Movement,” better known as the “New Negro Movement.” It would be a race conscious, internationalist, mass-based movement for “political equality, social justice, civic opportunity, and economic power” geared toward “the Negro common people” and urging defense of self, family, and “race” in the face of lynching and white supremacy.2When his Harlem Casino lecture series ended in late February 1915, Harrison offered his explanation of the racial significance of the war to white audiences at the Brownsville (Brooklyn) Radical Forum in three lectures on the European conflict. One talk focused on the immediate causes of the war and on Heinrich Gotthard von Treitsche, the outspoken advocate of Anglo-Saxon superiority, from the University of Berlin. Harrison followed these presentations with three of his more popular lectures: “Lincoln and Liberty,” “Sex, Sinners, and Society,” and “Education out of School,” the last probably being an elaboration of his views on education coupled with encouragement of self-education efforts. His talk on self-education was apparently well received because the next year, when he was scheduled to speak on the subject, the Monatlisches Zeitung Turn-Verein Vorwarts of Brooklyn raved, “No speaker in the country is better qualified to treat this topic and the lecturer’s personality and style bespeak a very enjoyable and instructive evening.”3

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.