History

Baltimore Riot 1861

The Baltimore Riot of 1861 was a violent clash between Confederate sympathizers and Union soldiers during the American Civil War. The riot erupted when Union troops attempted to pass through Baltimore on their way to Washington, D.C. and resulted in the deaths of several soldiers and civilians.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

3 Key excerpts on "Baltimore Riot 1861"

- eBook - ePub

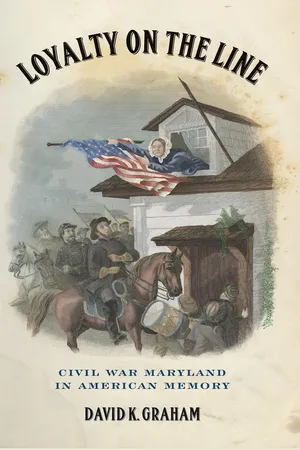

Loyalty on the Line

Civil War Maryland in American Memory

- David K. Graham(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- University of Georgia Press(Publisher)

FIGURE 1.1. Rioting in Baltimore, April 19, 1861, by Currier & Ives (courtesy of the Library of Congress).The following day Hicks penned a letter to Secretary of War Cameron in which he outlined the challenges he was facing in the secessionist stronghold city. He confessed that “the rebellious element had the control of things. They took possession of the armories, have the arms and ammunition.” Lincoln wrote Hicks the same day requesting his immediate presence along with the mayor of Baltimore in Washington to discuss issues “relative to preserving the peace of Maryland.” The Baltimore Riot and the need to control “the rebellious element” in Maryland moved to the forefront of the federal government’s consciousness within the first few weeks of the Civil War.17The Baltimore Riot not only started speculation on Maryland’s loyalty; it was also often a point of contention for those who debated the state’s wartime position well into the twentieth century. The city, in particular, was on the lips of both Confederate and Union sympathizers. Those who believed in the Confederate cause upheld Baltimore as a shining example of devotion in the face of intense opposition. Conversely, Unionists loathed Baltimore and its citizens for their rebellious spirit. The riot added another dynamic to these debates and was used by both sides in an attempt to prove Maryland’s true Civil War identity.Hicks faced other pressing issues on the ground in Maryland and ultimately decided to move the General Assembly west to Frederick and discuss the course Maryland should take while Lincoln made plans for occupying and securing Maryland under federal control. The decision to move the legislature was due in part to federal occupation of Annapolis, and Hicks also later pointed to the large pro-Union population in Frederick as the primary factor in his decision. The session was called on April 22 in order to decide on a policy of secession or loyalty to the Union. On April 27, the Maryland Senate and House of Delegates resolved that the state would not secede and informed their constituents that any fears of such an action were “without foundation.” The legislative body understood they had “no constitutional authority to take such an action.” The General Assembly also approved a bill on behalf of the City Council of Baltimore “for the defence of the city, against any damage that may arise out of the present crisis.”18 - eBook - ePub

Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War

The Trials of John Merryman

- Jonathan W. White(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- LSU Press(Publisher)

BALTIMORE IS TO BE THE BATTLEFIELD OF THE SOUTHERN REVOLUTION ” The Baltimore Riot and the Formationof Lincoln’s Habeas Corpus PolicyWhen Abraham Lincoln received word on April 14, 1861, that Fort Sumter had fallen into Confederate hands, he set to work with his cabinet to formulate a policy that would sufficiently respond to the crisis. Seven Deep South states had already seceded from the Union. Now these so-called Confederate States had attacked the nation’s flag, affronted the national honor, and forcibly seized federal property. The president needed to respond decisively. On April 15, Lincoln issued a proclamation calling forth seventy-five thousand militiamen from the states and summoning Congress to convene in special session on July 4, 1861.1Lincoln’s proclamation was greeted with disillusionment and anger across the Upper South. His call for troops was evidence to Virginians that he really sought the “subjugation of all who would not subscribe to the creed of the conqueror.” On April 17, the Old Dominion State voted herself out of the Union. Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee soon followed. For Lincoln, the slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri now needed to be held at all costs. Indeed, Lincoln believed that losing the border states would mean losing “the whole game.”2 If Maryland fell to the rebels, the national capital would be impossible to defend.Maryland, a border slave state, sat in a precarious position in the spring of 1861. Geographically, Maryland linked the North to the nation’s capital. Strategically, northern soldiers could not reach the District of Columbia except by train through Maryland. The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad ran from Philadelphia to Baltimore, while the Northern Central Railway Company’s lines linked Harrisburg to Baltimore. From the west, the Baltimore and Ohio brought travelers to the Monumental City. Passengers on these trains could then head south to Washington on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad from Camden Station, near the harbor. - eBook - ePub

Revolting New York

How 400 Years of Riot, Rebellion, Uprising, and Revolution Shaped a City

- Sapana Doshi, Mathew Coleman, Neil Smith, Don Mitchell(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- University of Georgia Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 6America’s Deadliest Riot

The 1863 Draft Riots RACHEL GOFFE AND ESTEBAN KELLYAmerica’s deadliest riots were not simple, straightforward struggles between two opposing sides. The conditions that sparked them arose from a complex layering of New York’s political factions, classes, races, ethnicities, and investments amid the country’s brutal civil war. As the economic crisis of 1857 abated, a political crisis over slavery and secessionism grew. As abolitionist and anti-abolitionist divides deepened through the city, growing class and race resentments smoldered and finally burst into flames when authorities tried to implement a federally mandated draft. Manhattan burned for days, only to emerge with its geography forever restructured.But first there was an election. New York was a unionist city during the Revolution (chapter 4 ), but it was a Union city during the 1860 election. A fusionist, Democratic, Union ticket (i.e., favoring the interests of the southern states) prevailed in the city on Election Day as its residents, egged on by “the Mercantile and Capitalist classes” (as the Republican Tribune put it), voted overwhelmingly against Lincoln. They were, however, outvoted by Republicans upstate, and Lincoln won the state and, with it, the presidency.1Merchants and bankers, fearing war and the loss of their southern markets, soon met in large numbers to consolidate their interests. Specifically, they passed resolutions of solidarity with the South, including affirmation of the “superiority” of the white race and support of the rights of slaveholders, preferably within the Union but as a separate Confederacy if necessary. Within six weeks of the election, South Carolina had seceded; less than two months later, the breakaway Confederate States of America had been declared, and war was inevitable. So too, perhaps, was another economic crisis in the city, as the Confederacy quickly repudiated its northern debts and expressed its venom against New York capitalists’ creaming of excessive profits off the cotton sent to Europe.

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.